|

With pandemic experience under our belts, going into work while sick seems ludicrous or even dangerous. But in truth, it used to happen all the time. Co-workers sniffling through meetings or clients coughing in the boardroom were commonplace occurrences, even if misguided. But today, in this pandemic-centric world, is going to work sick ever OK? Are these little sniffles and coughs acceptable in places of work?

We spoke to more than 1,000 employed Americans to find out if it will ever be OK to work on-site while under the weather. We asked them to confess how often they had done so before and how the pandemic changed their approach. They also shared the reasons and circumstances in which they felt it was still acceptable to go to work while showing symptoms, even today. If you've already returned to the office or your workplace is just starting to open their doors, you may want to know what you're in for. Just keep reading to find out.

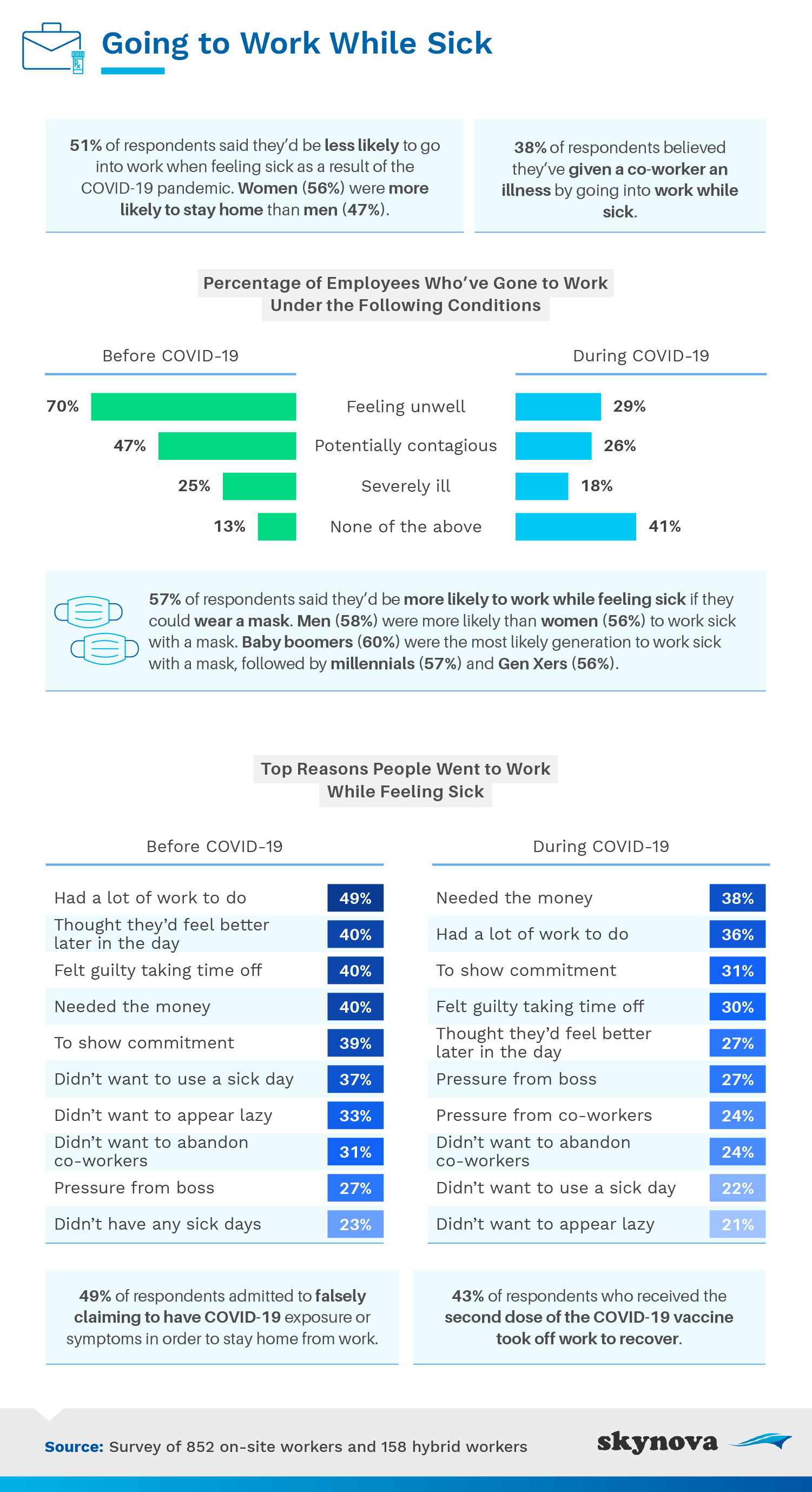

First, our study kicks off with a look at how often people have ever gone into work sick and why. We also reported the percentage of people who have gone to work sick since COVID-19's onset and their reasons for doing so. We even considered antagonistic behavior or avoiding work due to a fake illness.

Going to work sick was incredibly common before COVID-19. Seven in 10 employees said they have worked while feeling unwell, with 47% of them estimating they were contagious at the time. While a global catastrophe may not have been on their mind, the workforce wasn't exactly healthy before the pandemic and certainly needed employees to look out for one another. Pre-COVID studies estimated that employees were already becoming increasingly unwell, with more than half suffering from what we now call a "preexisting condition" and 38% suffering from excessive pressure on the job.

As we now know, obesity and other commonplace preexisting conditions make contracting COVID-19 incredibly dangerous. Even so, 29% of employees admitted to going to work while feeling sick since the pandemic began. More than a quarter assumed they were contagious, and 18% even said they were severely ill. Though this represents a significantly lowered likelihood of attending work while sick, it's certainly not unheard of.

Of course, why a person would do this was our next question. The No. 1 reason people still went to work while sick during COVID-19 was that they needed the money. Prior to the pandemic, their primary reason for doing so was that they had a lot of work to do. Considering the economic fallout of the pandemic and the Depression-era levels of unemployment, it is perhaps inevitable that financial concerns were the primary driver of people still going to work sick in a post-COVID world.

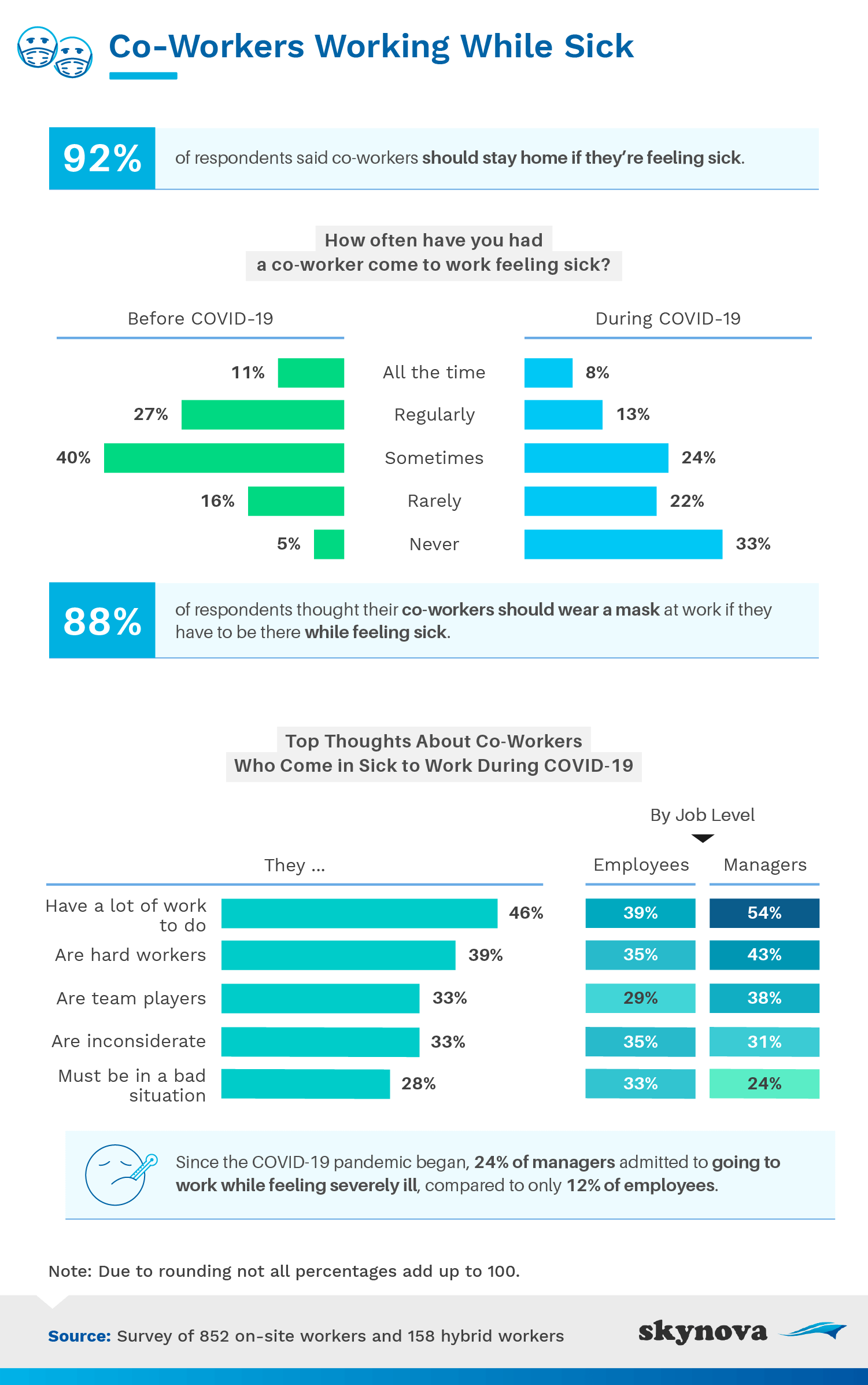

Although many respondents admitted to going into work sick even since the pandemic began, we wanted to know how they were perceiving others doing the same thing. What do people assume when they see a sick co-worker? Do they think the person should be there or perhaps be wearing a mask? The next part of our study answers these questions.

In spite of the fact that only 41% of respondents could say they had not gone into work while feeling sick symptoms since the pandemic's onset, an overwhelming 92% agreed that you should not do this. In other words, there is clearly a "do as I say and not as I do" mentality at play here. This is also a primary concern with new mask regulations: Even though you are required to have been vaccinated to go mask-free, there's really no feasible verification process. Those who aren't vaccinated can lie about their status. As The Washington Post puts it, they "won't really even have to do that; they can just take off their masks." Considering the results of our study, this is likely a very common behavior, though most would agree you shouldn't.

If you do go into work sick, you'll probably receive a variety of judgments. Exactly a third would assume that you're inconsiderate, while another 39% felt it meant you're a hard worker. A third would also see you as a team player, while 28% would assume you were in a bad situation financially. If you're a manager, perceptions of your decision to go into work while sick seem more positive.

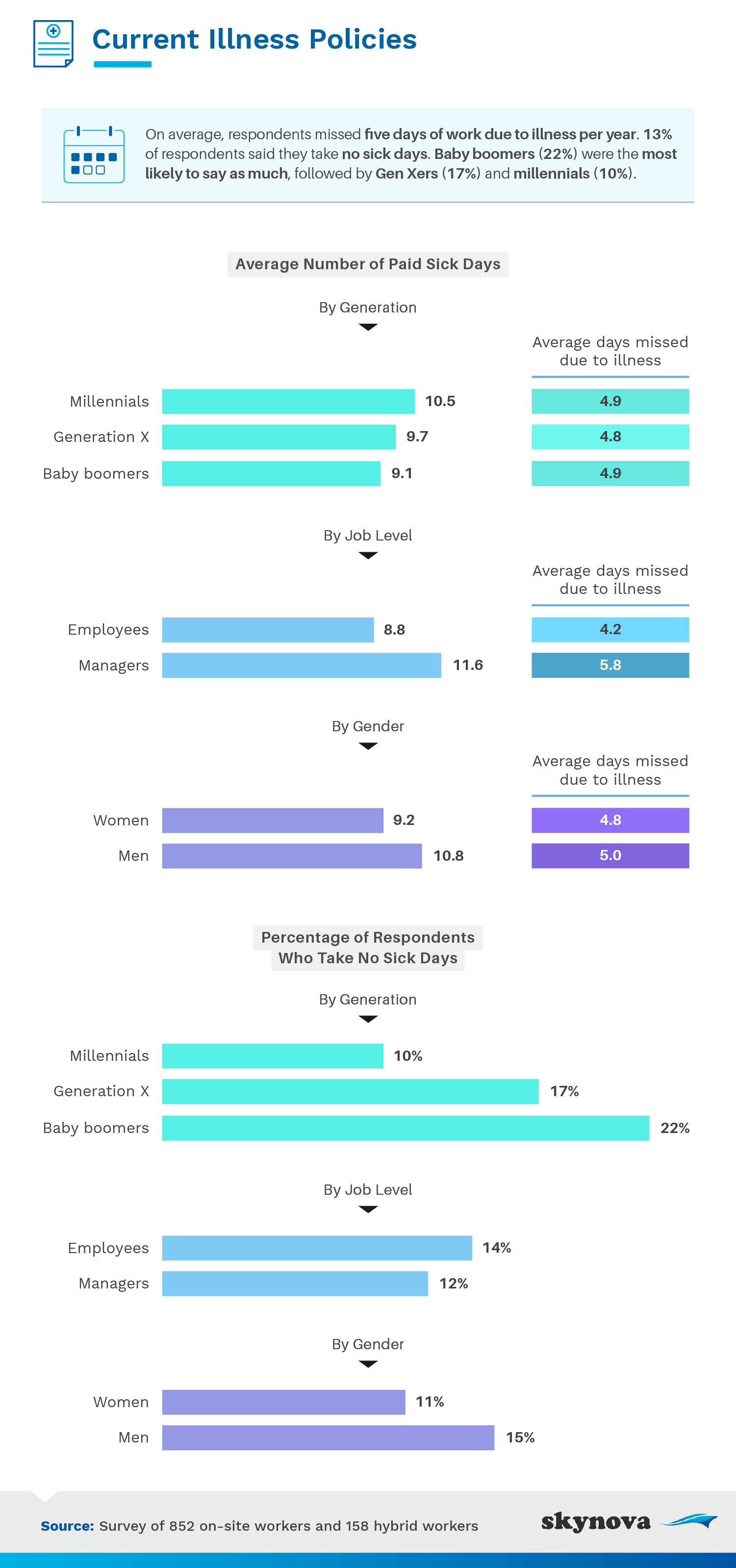

Clearly, the pandemic is changing the behavior of sick employees, but what do the policies around illness actually mandate? The next piece of our study asks employees how many paid sick days they receive and how many use them. Responses were broken down and analyzed by generation as well.

On average, respondents reported missing five days of work due to illness each calendar year. They also reported having an average of 10 paid sick days at their disposal, meaning a substantial percentage of sick days were left on the table. These days left on the table become even more significant when you consider how often employees are still going to work sick.

Generational differences also highlighted a concerning issue. Baby boomers, who were the most likely to be in the high-risk category, also had the lowest number of paid sick days, on average. While millennials received 10.5, baby boomers received just 9.1. Moreover, baby boomers were also the most likely group to say they took no sick days whatsoever over the course of a year. Perhaps they have relatively crucial roles at work or more financial pressure to concern themselves with. Whatever the reason, there are clearly issues with people coming into work sick that still need to be resolved.

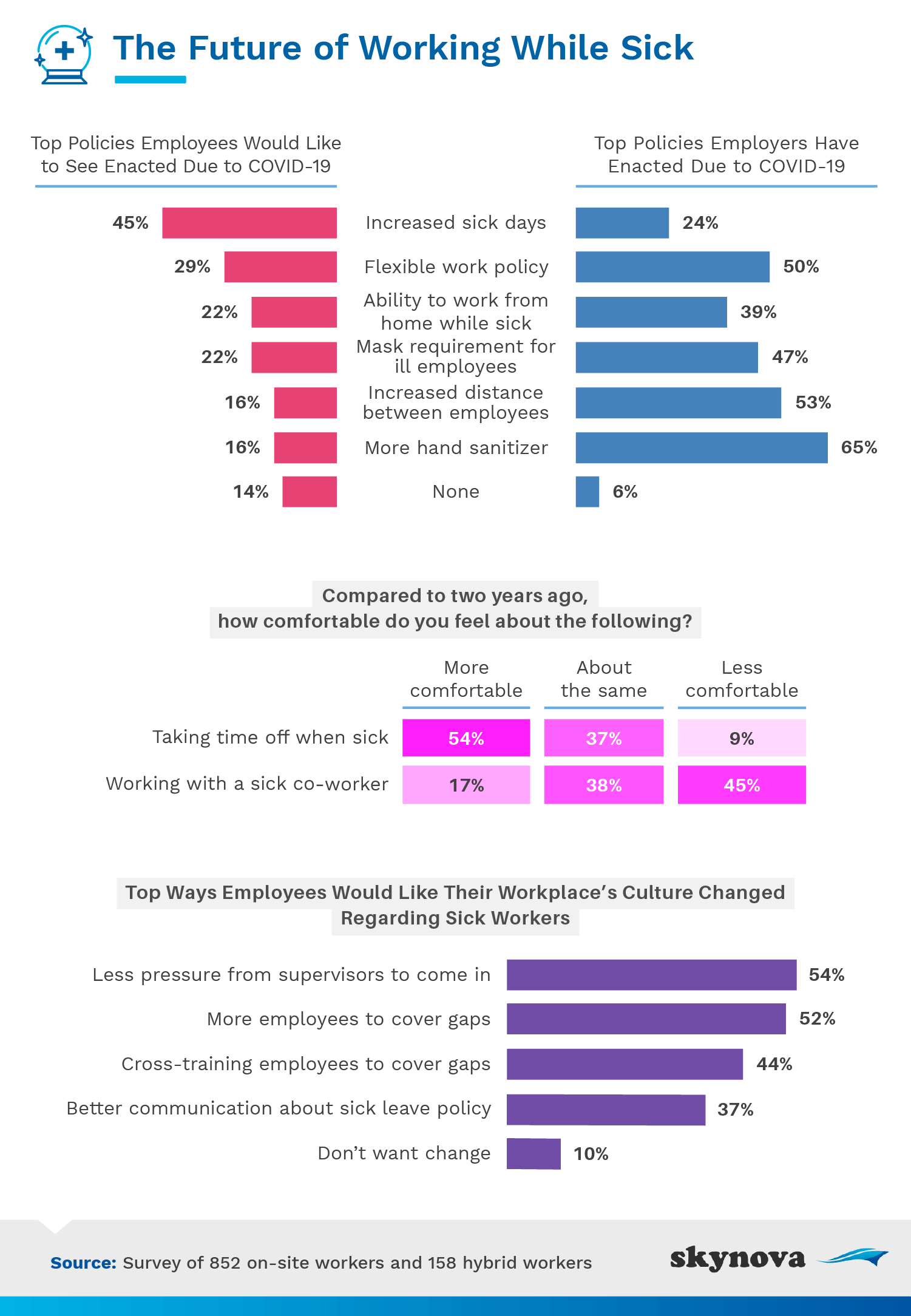

So what do these numbers ultimately indicate? What will the future of working while sick look like? The last part of our study asked respondents to share the policies their employers had enacted since COVID-19 started, the policies they'd like to see enacted, and how they'd like to see the overall office culture change.

Most employees (45%) simply wanted more sick days at their disposal, though only 24% had actually seen this policy enacted since the health crisis began. More often, offices were just offering hand sanitizer (65%) or putting more physical distance between employees (53%). While these policies are beneficial, they are not nearly as effective as letting an employee stay home and avoid co-workers completely while symptomatic.

Moreover, 45% of employees felt less comfortable working with a sick co-worker, compared to two years ago. Policies should reflect this toward encouraging sick workers to stay home when possible. After all, when we asked about the top cultural changes employees would like to see, their No. 1 response was to feel "less pressure from supervisors to come into work while sick." If policies changed to reflect the need to stay home while sick, perhaps this pressure would naturally relieve itself.

Evidence revealed there's ultimately a very fine line between working responsibly and irresponsibly while sick. After all, those who came into work while symptomatic weren't doing it just for fun: They most often reported desperately needing the money or feeling pressure from supervisors to go in anyway. Even when employees noticed a co-worker who was sick, they related all too well and often judged the person in a positive light for doing so.

There was, however, an awareness of these issues. Employees had many cultural and policy changes in mind, namely easing the pressure to continue working while sick and perhaps offering a few more paid sick days. Getting employees to actually take the sick days may involve another host of challenges. But considering the risk you pose to others when under the weather, especially in a post-COVID world with remote opportunities, stay home and get some rest.

Always on the side of the small-business owner, Skynova seeks to share this type of information to help even microbusinesses see success. Skynova offers easy-to-use, professional invoicing so that small businesses can get paid faster, bill anytime and anywhere, and stay organized.

We surveyed 1,010 employed people. Among them, 852 worked on-site, and 158 were hybrid workers (enjoying a combination of on-site and remote work). Among them, 56% were men, 43% were women, and 1% preferred not to answer. Respondents' ages ranged from 25 to 60 years old with an average age of 38.

For short, open-ended questions, outliers were removed. To help ensure that all respondents took our survey seriously, they were required to identify and correctly answer an attention-check question.

These data rely on self-reporting by the respondents and are only exploratory. Issues with self-reported responses include, but aren't limited to, the following: exaggeration, selective memory, telescoping, attribution, and bias. All values are based on estimation.

Feeling sick? Then stay home! You can help others by sharing the information found within this article all from the comfort of your couch. Just be sure your purposes are noncommercial and that you link back to this page.