|

If you’re working in the U.S., you’re probably familiar with burnout. Statistically speaking, Americans are much more likely to be burned out at this moment in history rather than not. But can it really all be blamed on the pandemic? Are most workers aware of their own plight? And are businesses aware of the consequences? We recently spoke to 1,000 working Americans to find out.

Ranging from entry-level employees through senior management, employees shared with us the symptoms they’re feeling and the solutions they’re trying with regards to burnout. As it turns out, yes, there are plenty of issues apart from the pandemic that have been contributing to employee burnout for quite some time – and some fixes that seem to work better than others. To see which types of employees, roles, and jobs are suffering from burnout the most and what answers most employees have, keep reading.

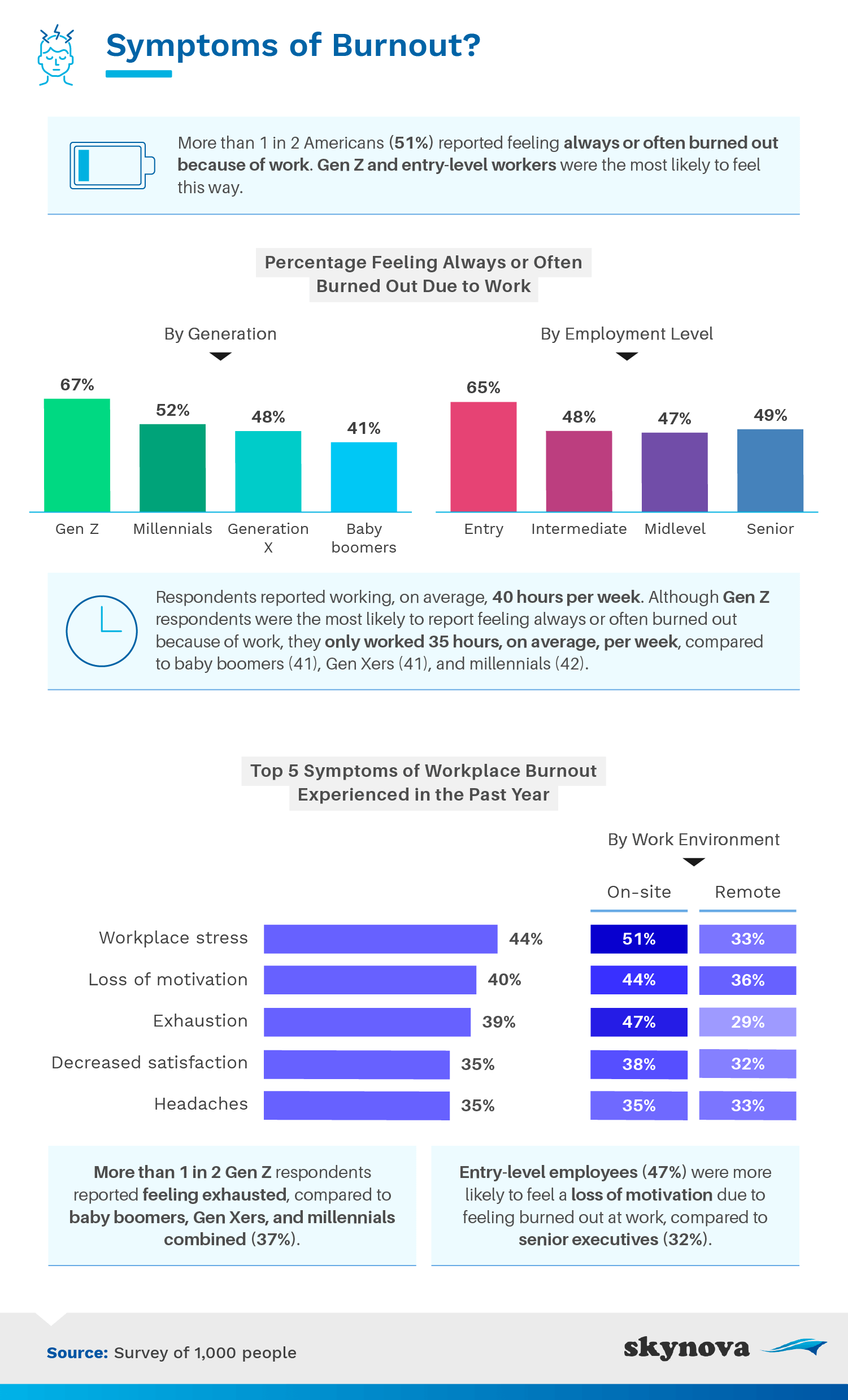

Our study begins with a simple but important question: Who is the most burned out? We asked each employee to answer how often they felt burned out specifically because of work. Their responses are broken by gender, generation, and levels of employment. Here, we also get into the most common symptoms of burnout that workers were noticing and compared responses by those working on-site and remotely.

Most Americans are feeling burned out, and they’re feeling it most of the time: 51% of employees said they feel burnout because of work “often” or even “always.” It was also the younger and newer employees that tended to bear this burden the most: The older a respondent was, the less likely they were to report feelings of burnout, while entry-level employees experienced burnout much more heavily than their senior counterparts. That said, burnout still plagued 41% of baby boomers.

Burnout most often manifested in the form of workplace stress (44%), a loss of motivation (40%), and/or a sense of exhaustion (39%). Burnout is actually a diagnosable condition, with chronic workplace stress being the primary cause. Reports of stress, however, were much more common for on-site workers than they were for remote employees. As it turns out, working remotely could reduce a worker’s likelihood of experiencing stress by 18 percentage points. In fact, on-site workers were more likely than remote workers to experience every symptom of burnout.

While remote work appears to correlate with decreased levels of burnout, the feeling certainly isn’t eradicated in this demographic. This next piece of our study digs into why, in their own opinion, professionals are reporting feelings of burnout.

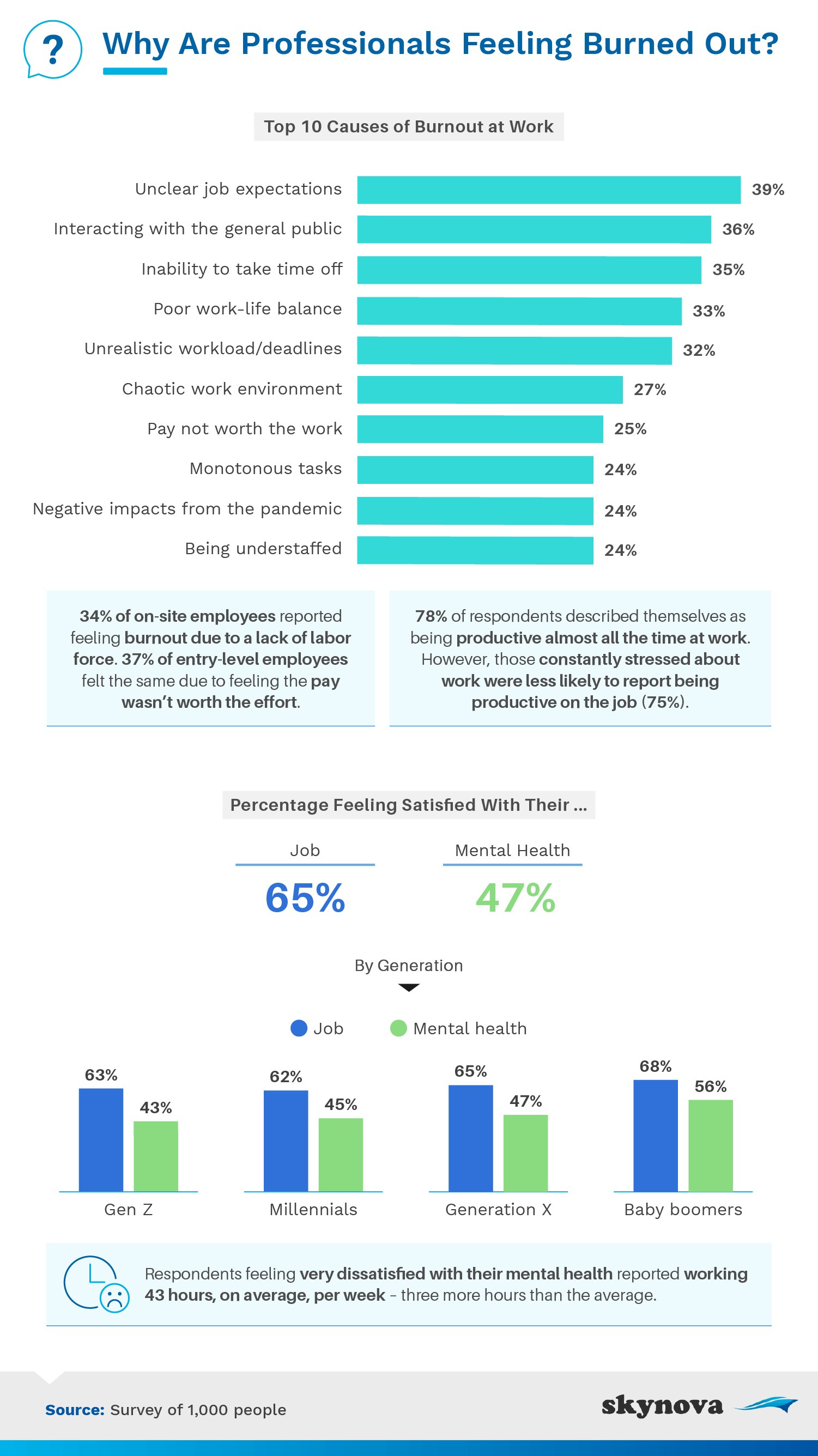

As intense as the pandemic was, there were many other causes that contributed more heavily to burnout in the eyes of employees. Unclear job expectations was the No. 1 contributor cited as causing burnout among working Americans. Things like having to interact with the general public and the inability to take time off also caused burnout for more than a third of workers.

Economists point to a host of reasons behind the labor shortage, from health risks and child care to a high percentage of furloughed workers who expect to be called back. The sense of the pay not being worth the work that more than 1 in 4 respondents shared is also likely a factor. Twenty-five percent agreed that this caused burnout, while another 24% specifically mentioned too few people working.

In spite of the high rates of burnout and catalysts for it, employees were managing to stay focused. Seventy-eight percent considered themselves to be productive almost all of the time at work, while 65% said they were still satisfied with their job. The severity of burnout’s impact seemed to mostly hit mental health, a crucial factor with which only 47% of respondents felt satisfied.

With so much burnout and so many causes for it, what are employees supposed to do? This next piece of our study looks at solutions employees have tried and the results they’re seeing. If you or someone you know is currently suffering, this is a pivotal piece of the study to read.

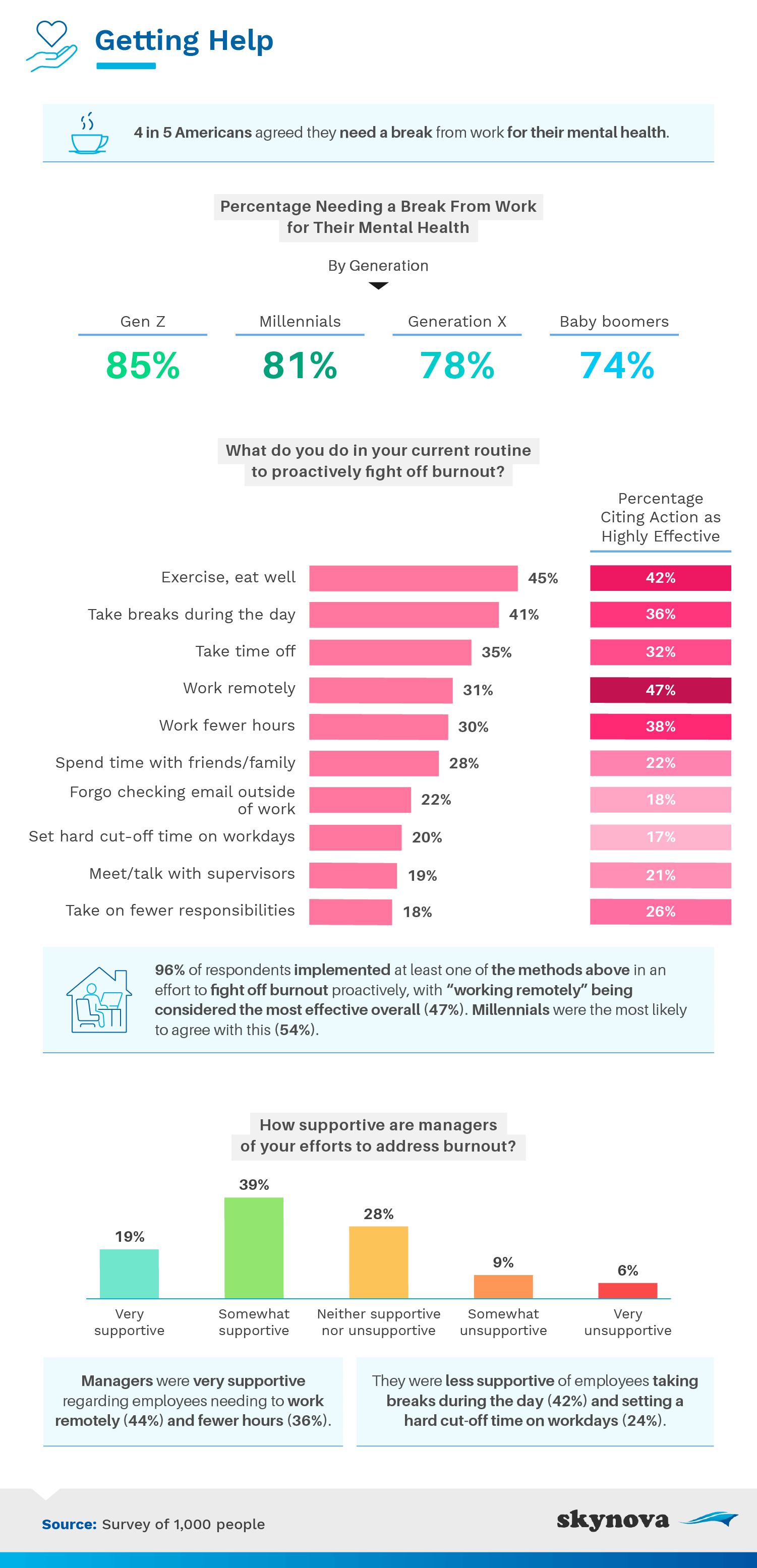

Working Americans appear in dire need of a break; in fact, 4 out of 5 agreed that they need a break from work specifically for the sake of their mental health. These numbers are unfortunately a sign of the changing times with regards to mental health. While only 1 in 20 adults struggled with mental health in the U.S. in 2019, that number quickly rose to 1 in 5 within a year. While a break may not feel possible for some workers, it does seem like a simple solution.

Of all the solutions we discussed, none of them were tried by the majority. But this isn’t necessarily a sign of laziness. Instead, mental health problems can make even the tiniest tasks extremely difficult to do, even if they would theoretically ease the issue. Forty-five percent were able to try eating well and exercising to combat burnout, which worked for 42% of those who tried it. The most effective method to ease burnout, however, was working remotely. If this is an option for an employee, evidence certainly makes a strong case for its effectiveness.

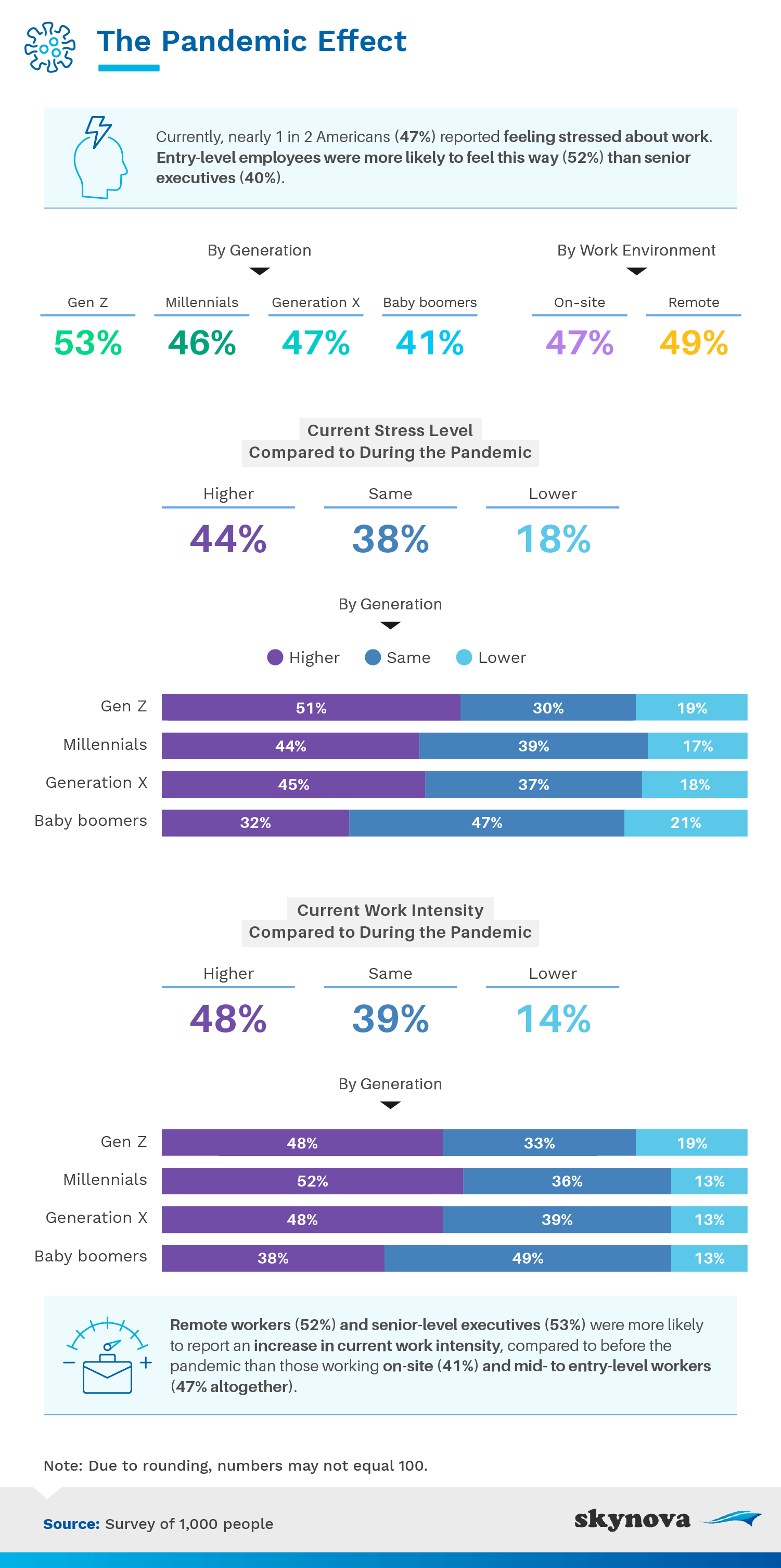

While the pandemic wasn’t entirely to blame for modern burnout levels, it certainly didn’t help. Our study concludes with a look into the comparative stress levels between now and pre-pandemic.

While we expected to find that the pandemic increased stress levels, we were surprised to see that younger generations were bearing the brunt of the increased workplace stress. The workplace became both much more stressful and much more intense for these younger workers since the pandemic’s onset. Even remote workers couldn’t avoid the added stress that came with the COVID-19 health crisis.

With regards to solutions for these Gen Z, millennial, and entry-level workers, most respondents agreed that money was the answer. While 48% of entry-level employees said increased salary would help their burnout, only 28% of senior-level respondents echoed the sentiment. Perhaps the stress that’s correlated with burnout is also correlated with financial strain. On-site workers were also more likely to feel that an increased salary would solve the problem.

Completely avoiding burnout seems unlikely, according to the evidence. Americans are more likely to feel burned out than not, and most of them feel this way most of the time. Remote work appeared to be one of the best tools at an employer’s disposal to dampen the burnout problem, while others mentioned just needing a simple break.

While the pandemic opened doors to remote work (which correlated with lowered symptoms of burnout), it also increased stress beyond what remote work could repair. Employees of all locations were feeling significantly more stressed since 2020. It was particularly younger employees, however, who felt this burden most heavily, often earning lower salaries and picking up the slack. For both the on-site and younger workers, more money seemed to be the answer to begin alleviating burnout.

Skynova provides online software like invoices, accounting, time sheets, and more for small businesses. In addition, we like to write in-depth articles about various topics we, and hopefully our customers, find interesting. They will generally have a business or workplace angle and often an intersection with another area of society (e.g., business and technology, politics, sports, health). The articles will be based on surveys, statistics, and research conducted by ourselves, something we think might be conducive to finding novel insights or perspectives.

We surveyed 1,000 people to explore how they currently feel about their job. Among them, 56% were men, and 44% were women. For generation breakdowns, the sample sizes were as follows:

For short, open-ended questions, outliers were removed. To help ensure that all respondents took our survey seriously, they were required to identify and correctly answer an attention-check question.

These data rely on self-reporting by the respondents and are only exploratory. Issues with self-reported responses include, but aren’t limited to, exaggeration, selective memory, telescoping, attribution, and bias. All values are based on estimation.

If your readers are adapting to working from home, we encourage you to share the results of this study with them for any noncommercial use. We simply ask that you include a link back to this page in your story, so they have access to our full findings and methodology.