|

With record numbers of people quitting their jobs in the face of an incredibly scary economy, it’s normal to wonder what exactly is happening. In a time of such economic uncertainty, what motivations and circumstances underlie the act of walking away from a salary? And so often? After speaking to more than 1,000 people across the country — both employees and managers who have experience with quitting — we have some answers.

Quitting can be a life-altering decision, whether you do it in a fit of rage or after careful planning. This first piece of our study looks into exactly how quitting went for respondents: Did they find something better? Or did they end up wanting their old job back?

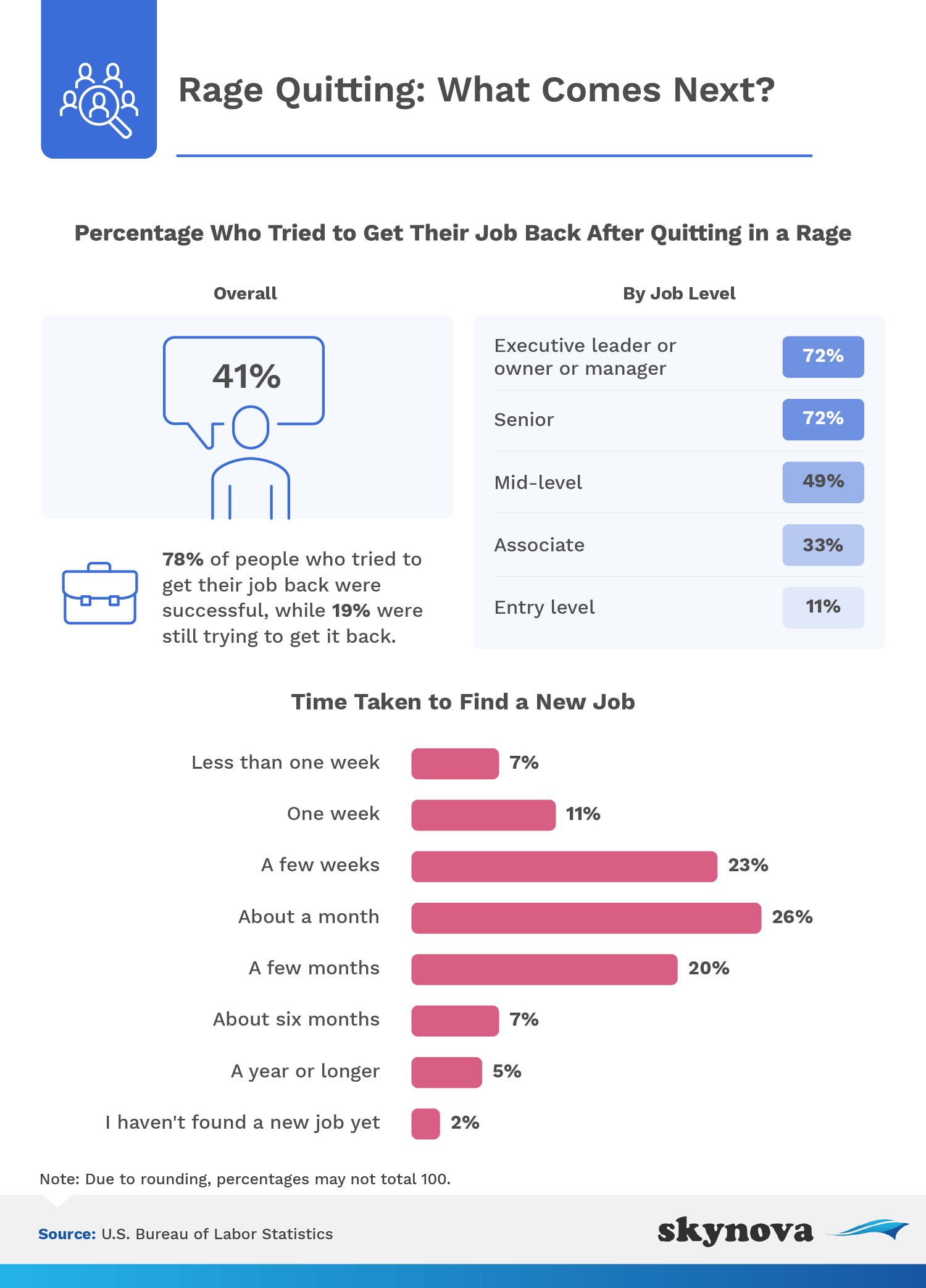

Quitters beware: The decision usually comes with its fair share of regrets. Forty-one percent of people who quit also actively attempted to get their old job back. While 78% of people who wanted their job back were successful in fulfilling that desire, it clearly wasn’t their mindset at the time of quitting. Evidently, their (temporary) experience in the world of unemployment or with their new job was not what they envisioned.

Trying to get an old job back after quitting was even more of a common phenomenon the higher people were up the corporate ladder. In other words, higher-ups were the most likely to ask for their old jobs back after leaving. Associate and entry-level positions were less attached and mostly stayed the quitting course.

Leaving a job also comes with its fair share of emotions, especially if you’re the one quitting. This piece of our study looks at how both salaries and emotions changed for respondents after leaving a role.

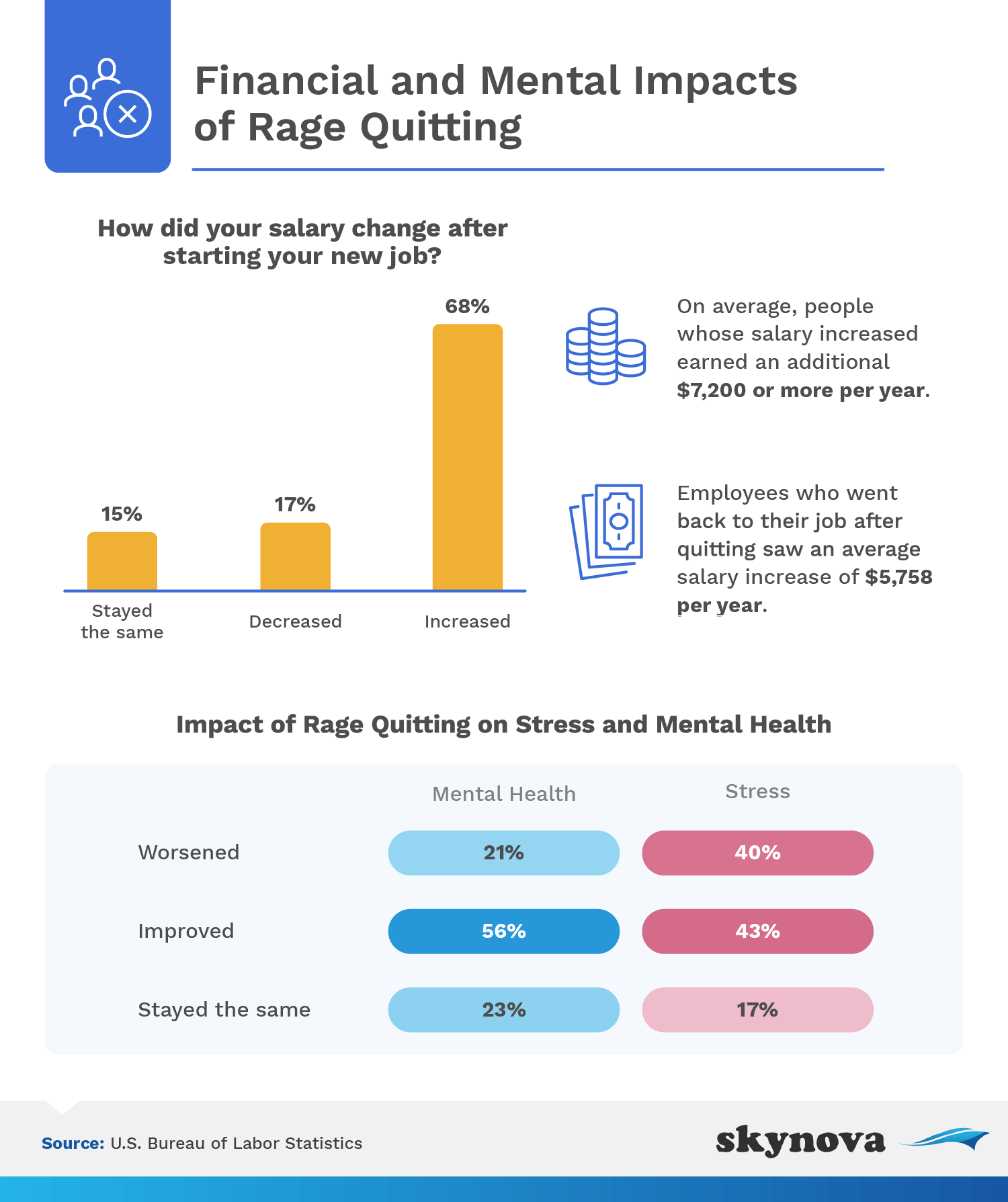

Even though quitting can be scary and can often lead to people asking for their job back, those who quit and stayed the course were often rewarded financially in the end. On average, quitting correlated with a higher salary for 68% of respondents, which came to an average of $7,200 annually. Assuming an average salary of $52,000 in the U.S., this represents nearly a 14% average salary increase for those who quit.

But money was far from the only consideration after quitting. Both mental health and stress were drastically impacted for most respondents, sometimes positively, sometimes negatively. While it was more common for mental health to improve after quitting (56%), about a fifth of respondents claimed their mental health got worse. Moreover, 40% said they felt their stress levels increase after quitting as well. This may shed light on why it was so difficult for many to pursue a new role and why they instead sought to regain their previous position.

With so much at stake in this turbulent economy, we wanted to know what motivations were strong enough to convince a person to leave their place of employment today. We asked about their most common and most pressing reasons for quitting.

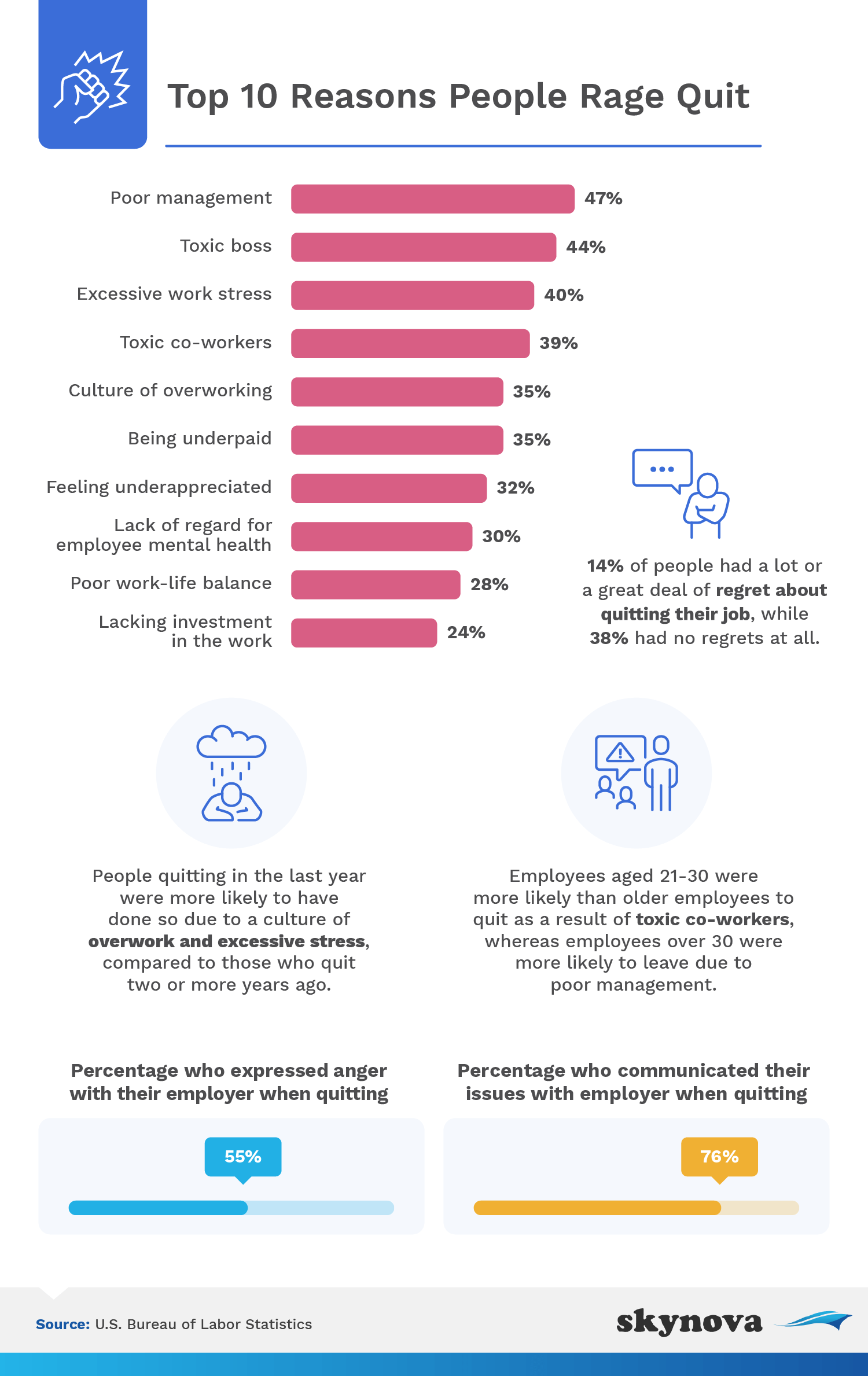

Employers were the number one and two most common reasons for employees to quit today: The employer either offered poor management (47%) or the boss was completely toxic (44%). Especially in the last year, which saw record highs of inflation and unemployment, employees were less likely to stay with employers who disregarded mental health. In other words, the boss is extremely influential in today’s workplace.

| The boss can be extremely influential in preventing today’s workplace turnover. |

With these types of catalysts for quitting, employees also commonly mentioned a wave of anger surfacing when they quit. In fact, more than half of respondents said they actively expressed their anger as they left. And more than three-quarters at least voiced some issues. These emotions weren't always handled professionally — far from it.

While we’ve dug into what quitting looks like after it happens, we have not yet looked at the actual process and conversation of quitting itself. This piece of our study asks about the specifics, like how people quit and how their employer reacted.

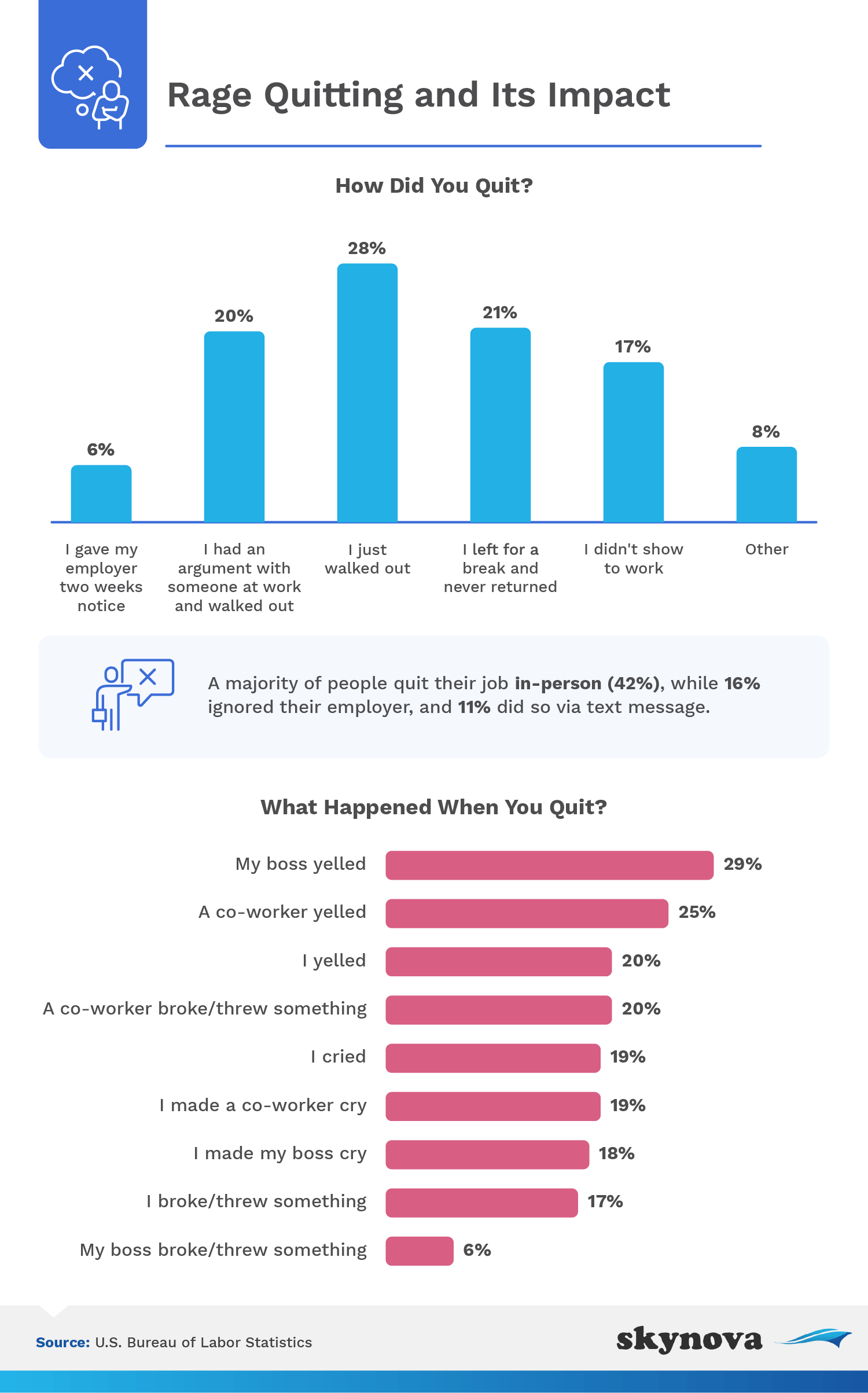

In true "rage quit" fashion, most employees chose to simply walk out on their positions. Twenty percent even said they first had an argument with someone and then stormed out. Only a scant 6% were able to say they gave their employers the standard two weeks’ notice. And more than 1 in 10 quit by completely ignoring their boss.

When people quit this way, emotions were certainly running high. Twenty-nine percent said their boss yelled; 25% said a co-worker yelled; and 20% said they themselves yelled. Unfortunately, it wasn’t uncommon for things to get even worse from there. One in 5 said a co-worker threw and/or broke an object, while 17% engaged in such behavior themselves. Eighteen percent said they even made their boss cry. The fact that so many ended up asking for their jobs back further suggests how bad the resulting experience was for them.

With so many employees citing their bosses specifically as their reason for quitting, we wanted to know what supervisors had to say. This last piece of our study solely looks at responses from those who are in charge of managing staff in some way.

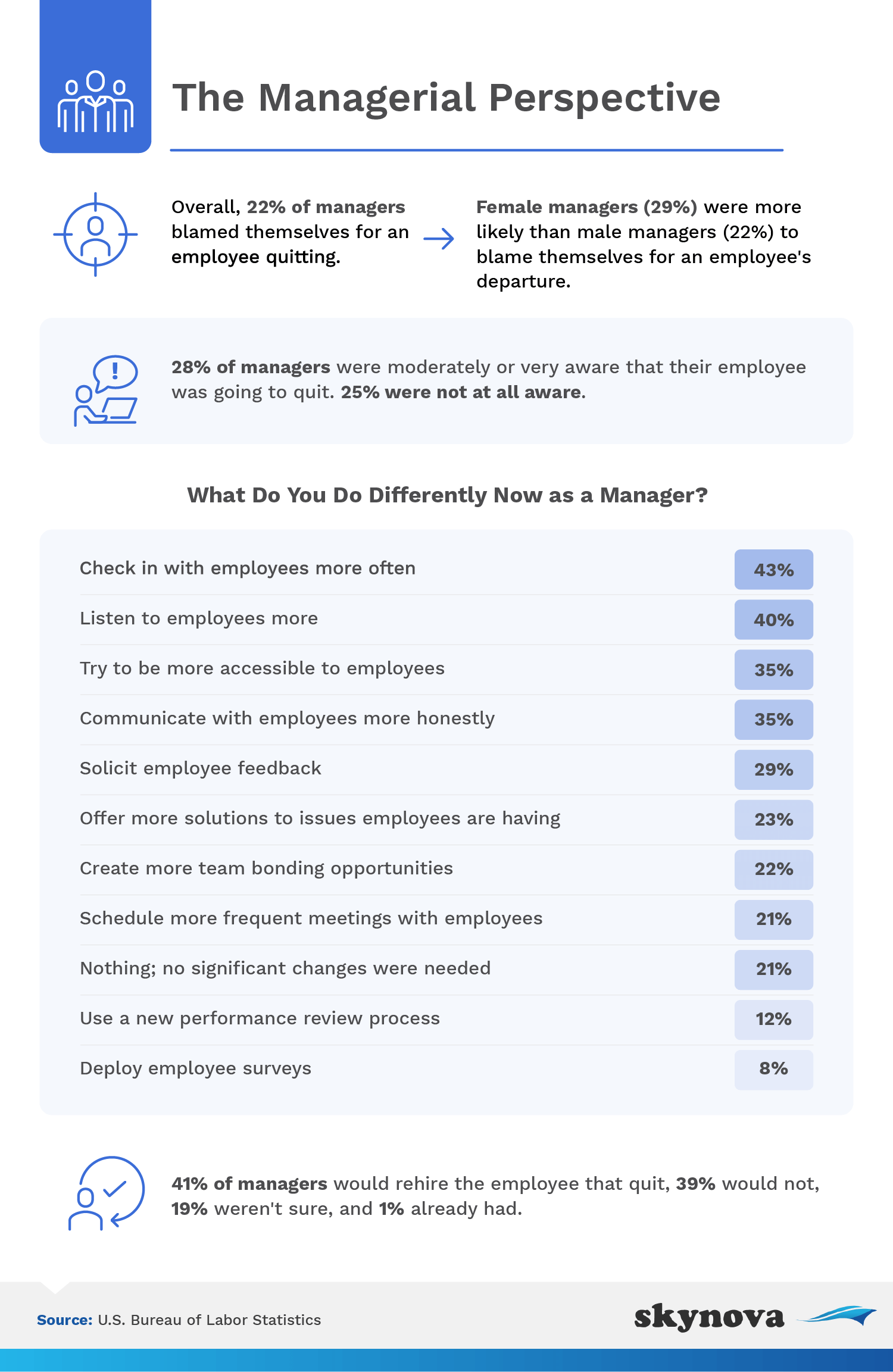

Managers were often understanding of their role in the quitting issue and actively took steps to fix their approach. More than 1 in 5 said they tended to blame themselves when an employee left, and 41% were more than happy to give the employee who quit their job back should they ask. That said, it’s clear a fair number of bosses did not assume the blame and wouldn’t rehire someone who’d quit, while 19% remained uncertain on what they’d do.

More commonly, managers used the quitting experience to adjust their behavior. Forty-three percent said it made them start checking in more with their employees. Regular check-ins are known to increase employee engagement and overall relationship quality, so this was one positive outcome for the remaining employees. Additionally, 40% of managers said their employees’ quitting caused them to start listening more, and 35% tried to be more accessible and transparent.

Quitting today may not be easy, but it’s more common than ever before. Respondents were mostly fed up with toxic bosses and poor management, and many quit in a fit of rage that involved yelling and throwing things. For many who left, higher salaries and better futures awaited. Others returned to their former workplace, and managers often reported new tactics to make everyone’s experience better.

Skynova can help all aspects of your business run smoothly by providing affordable small business apps, including invoicing templates and accounting software.

For this study, we surveyed 705 respondents who had quit a job, as well as 301 managers who had employees quit on them, using the Amazon MTurk platform. 113 employees had quit within the past year; 206 quit within the last two years; 138 quit within the last three years; and 248 quit more than three years ago. Among employees respondents, 301 were women, 395 were men, and nine identified as nonconforming or nonbinary. Among managers, 177 were men and 124 were women. 192 respondents were aged 21 to 30 years old; 267 were aged 31 to 40; 173 were aged 41 to 55; and 73 were aged 56 or older.

To help ensure accurate responses, all respondents were required to identify and correctly answer an attention-check question. Participants incorrectly answering any attention-check question had their answers disqualified. This study has a 6% margin of error on a 95% confidence level for managers and a 4% margin of error on a 95% confidence level for employees. In some cases, questions and answers have been paraphrased or rephrased for clarity. The data rely on self-reporting, and potential issues with self-reported data include, but are not limited to, selective memory, telescoping, and exaggeration.

Sharing information and spreading awareness is often a key agent of change. If you’d like to see changes in the workplace related to this information, you are welcome to share this research. Just be sure your purposes are noncommercial and that you link back to this page.