|

Since 2020, the concept of a healthy "work/life balance" has become ubiquitous. The pandemic caused many people to begin working from home, where their phones and computers keep them connected to their jobs almost constantly. For some – especially those with family at home – working less became a necessity. The need to do business virtually also forced people to innovate, streamlining processes to require less time and labor. These changes have led many to question the 40-hour, five-day work week.

The alternative prospect of a four-day work week has become widely appealing. This year, employers who advertised a four-day week in their job postings received up to 30% more applications than those who didn’t. They also identified an increased need to improve employee retention, with people leaving their jobs in droves – more than half plan to switch jobs in the next 12 months.

Who stands to benefit most from a shortened work week? What might happen if that became the norm? To find out, we asked 1,001 employees and managers in the U.S. about their work life and productivity, including the types of challenges associated with working less, and if it might actually work.

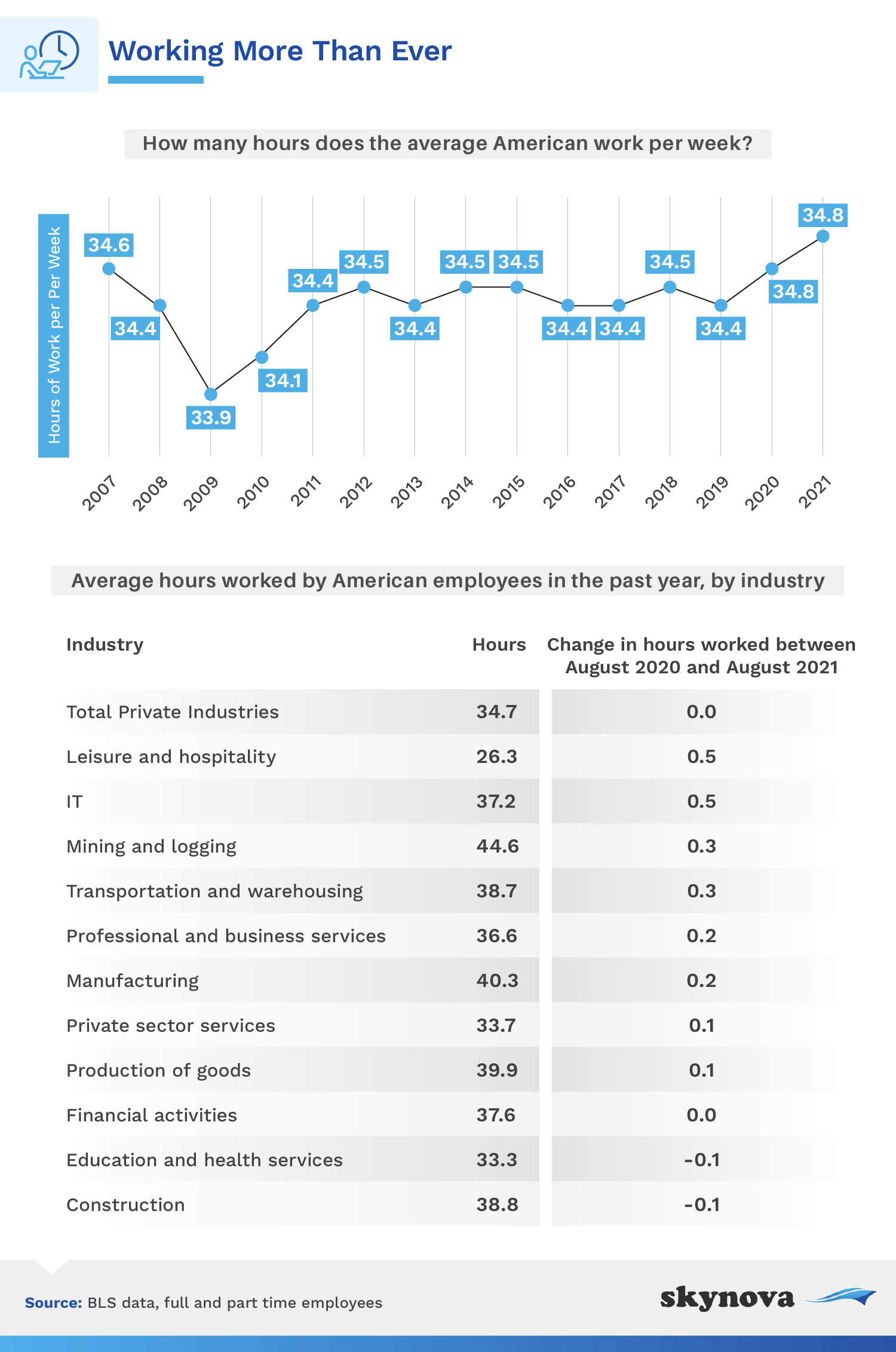

Considering how blurred work-life boundaries have become, it’s no wonder that people working from home ended up working more hours than they had on-site. Interestingly enough, the employees working the most hours were actually in industries that tend to require more on-site work.

Miners and loggers worked the most hours of all over the past year. They reported working an average of 44.6 hours per week as of August 2021 – about four hours more than manufacturing employees, who worked an average of 40.3 hours. Narrowing the work week down to four days might be more of a challenge for them than for education and healthcare employees, who reported working just 33.3 hours per week during that time.

Workers in the leisure and hospitality sector experienced the largest increase in weekly hours, tied with employees in the information sector. On the other hand, construction and education workers experienced a slight decrease.

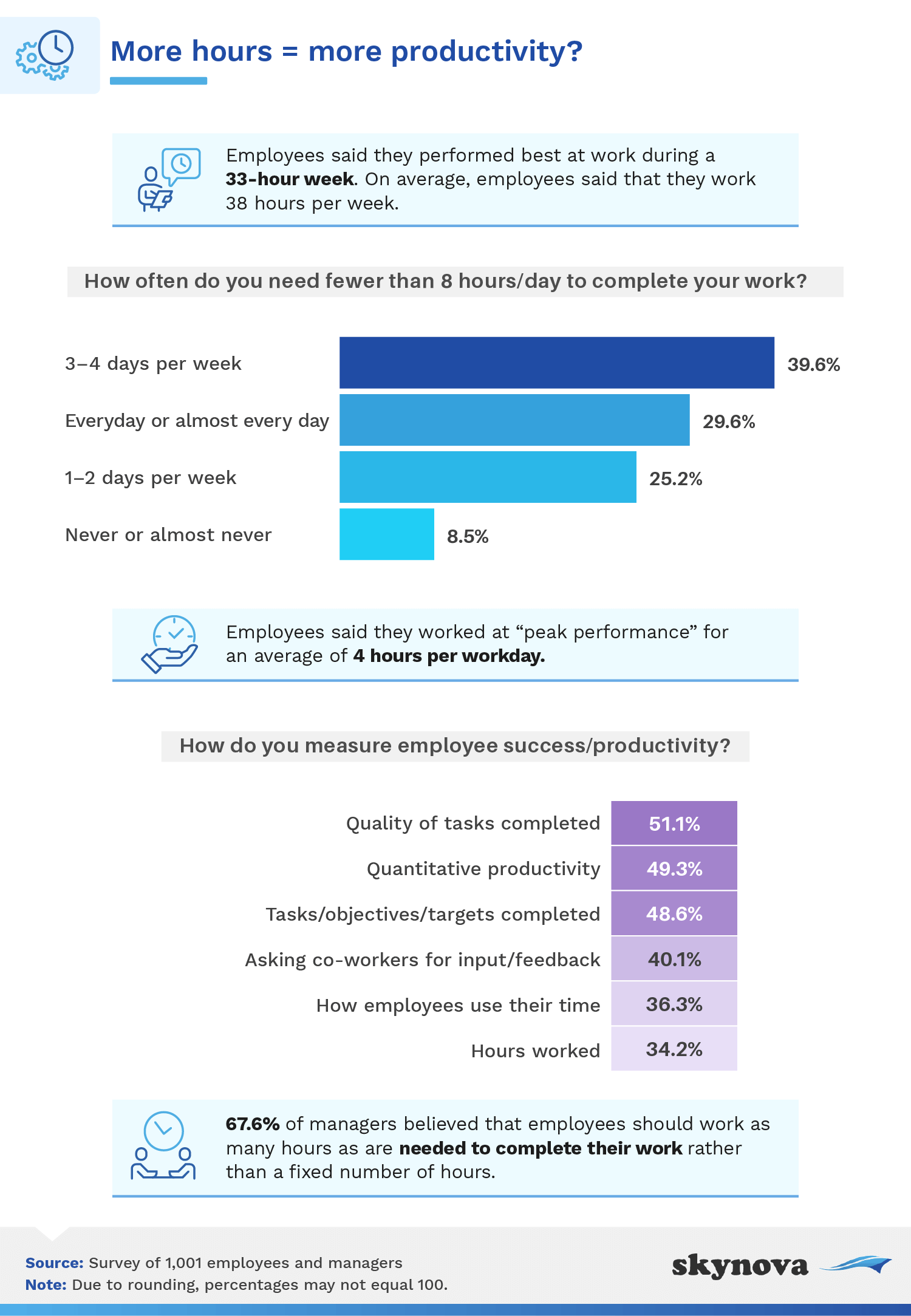

One might assume that working more hours means more productivity, but the truth is a bit more complicated. In fact, the health benefits of working fewer hours makes employees more productive at work.

When asked how many hours per week employees felt they were performing at their best, the reported average was 33 hours per week. That means that during a 40 hour work week, almost an entire workday is spent working at a less-than-optimal performance level. They also said they’re only at their best for four hours each day – half of a typical workday – with their productivity dwindling as the week progresses. Just over forty percent of respondents said they were most productive on Mondays, and 29.2% said they were least productive on Fridays.

In that case, it’s a good thing most managers felt employees should be able to head home as soon as their work is done: 67.6% said they believe employees should only work as long as it takes to finish the job, as opposed to a fixed number of hours. Another 51.1% of managers said they measure employee success and productivity by the quality of the tasks completed, while only 34.2% said they measure it by hours worked. The quality of the work was seen as more important than the amount of time an employee spends on it.

Still, many employees felt there often wasn’t enough time in the day to finish their workload. Over the past three months, 42.4% of employees had asked their employer to allow them to work more hours in order to complete their work, while only 14.5% asked to reduce their hours.

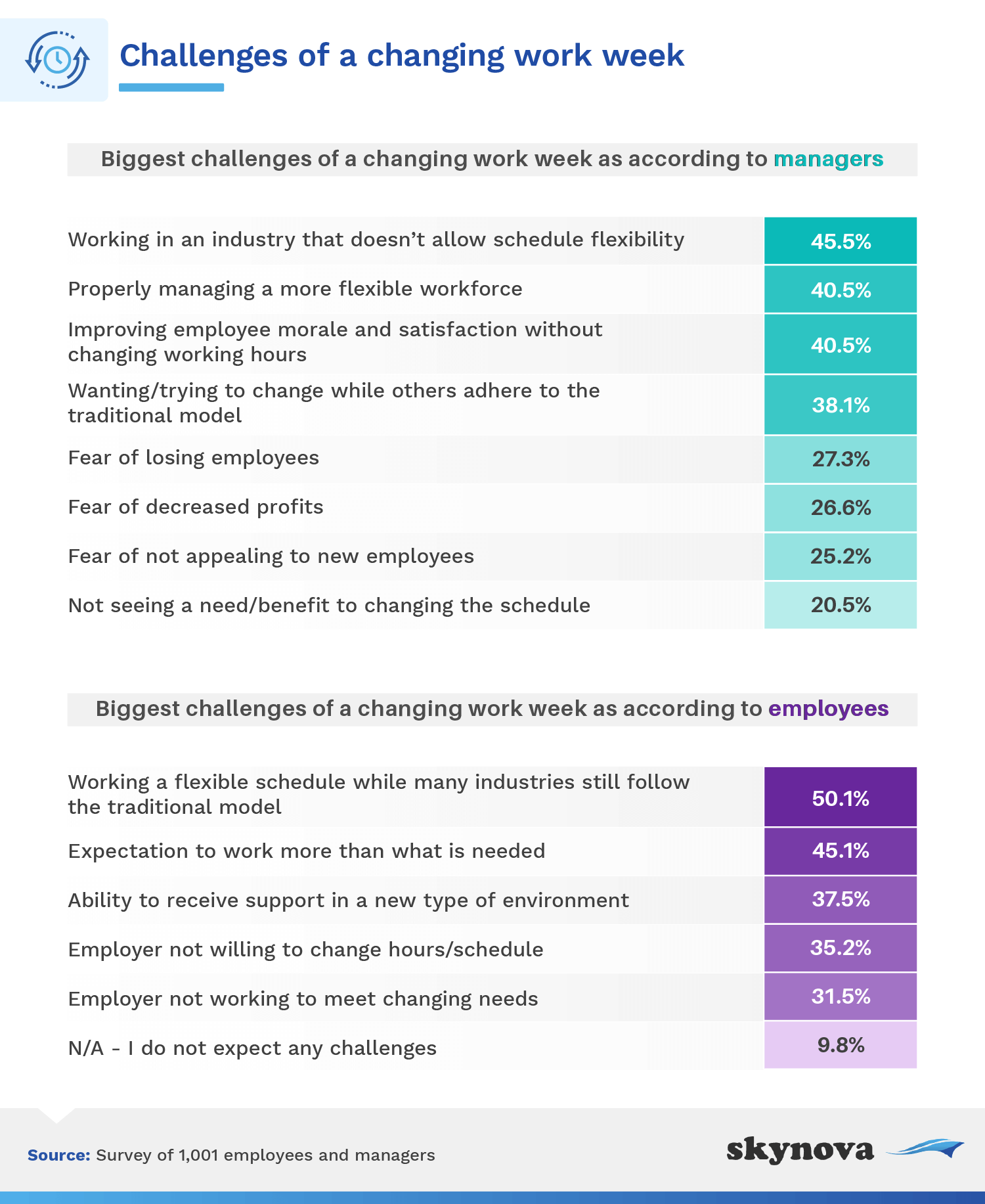

While limiting work hours clearly offers some benefits, most respondents admitted that there are also drawbacks.

The number one concern among managers (45.5%) was that their industry could not accommodate a flexible schedule or reduced hours. The second biggest concerns were a tie between being able to properly manage a workforce on a flexible schedule, and ensuring that employees would be satisfied with their ability to complete their work having less time.

For some companies, it’s important to be on the same schedule as those they do business with. This explains why more than half of millennials and Gen Z said their biggest challenge was working a flexible schedule in an industry that still follows the traditional work week, and more than half of respondents found it difficult to be available for businesses in other industries.

Flexible scheduling offers convenience, but it also has the potential for abuse. While it’s easier for employees to lie to employers about how many hours they’re working remotely, 45.1% of employees said their biggest challenge was being expected to work more than necessary. This was particularly an issue among baby boomers and Gen Z, as reported by 42.2% and 49.1% of them respectively.

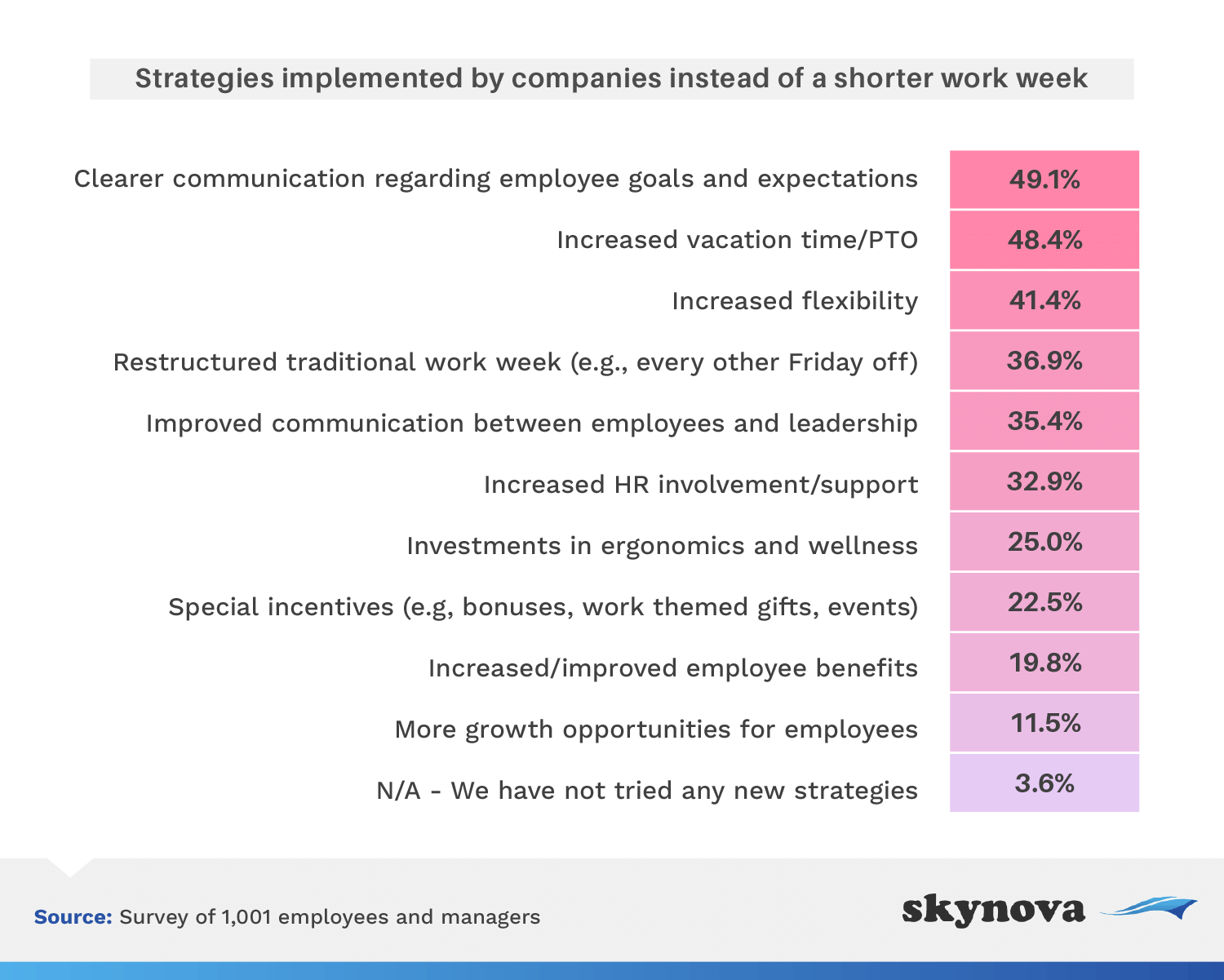

Employers might feel pressured to offer shortened work weeks, but for some, it’s simply not an option. Many chose to appeal to new hires or keep current ones on board using other perks. The top alternative method was fostering open communication: 49.1% of companies increased efforts to understand employees’ goals and expectations. The second most popular method was increasing vacation time or personal time off, which 48.4% have implemented.

Many of us see a three-day weekend as a rarity reserved for holidays and vacations. But what if we had one every week? We asked participants how they might structure their time,, and the issues it might cause.

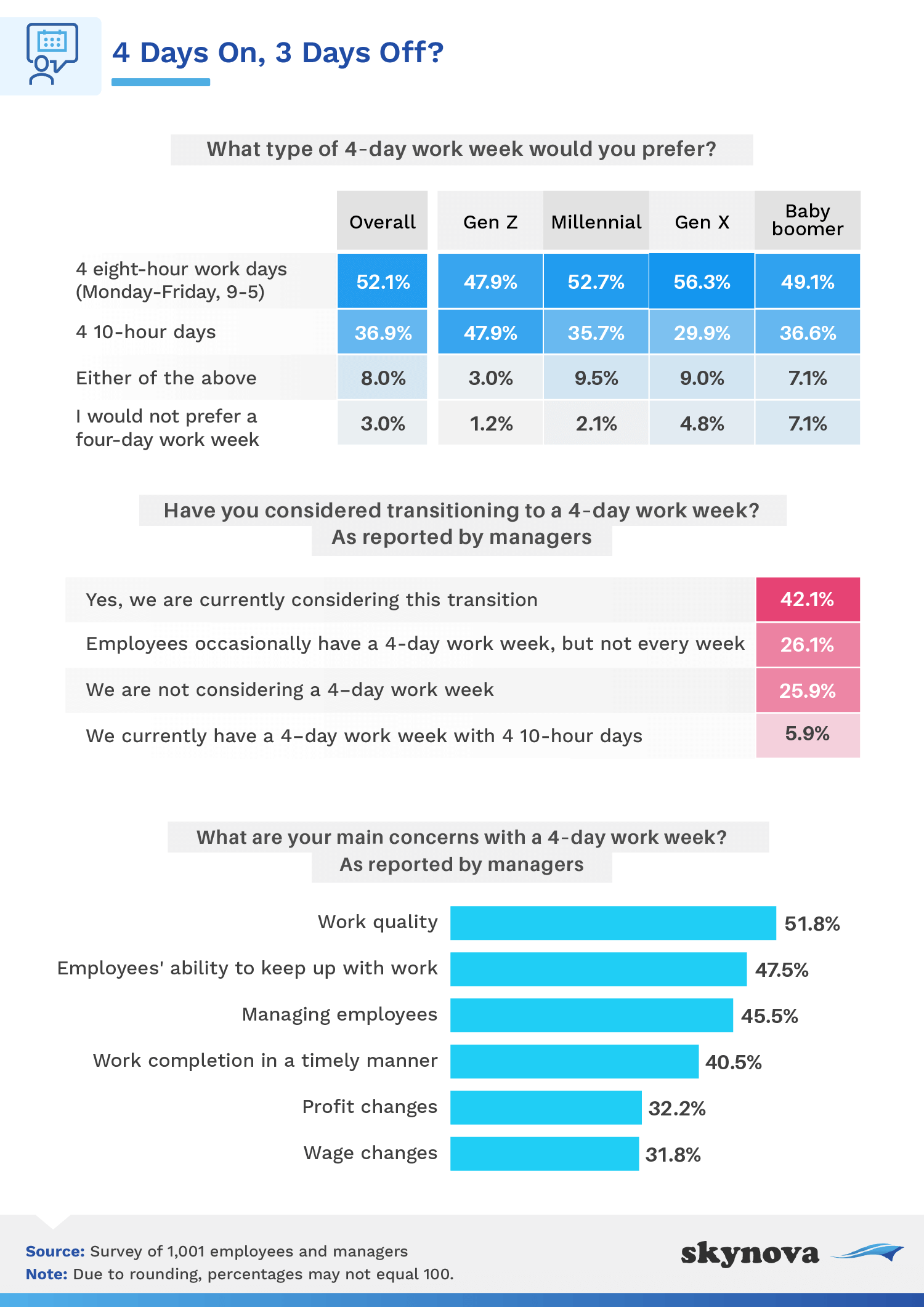

When asked what type of four-day work week they preferred, the majority of participants (52.1%) said they’d want to work four eight-hour days. However, just as many Gen Zers favored four 10-hour days as did four eight-hour days, while the rest significantly favored eight-hour days over 10-hour days. Surprisingly, the youngest participants were more interested in working a 40-hour week than the older generations.

Even though 51.8% were concerned with how a four-day work week might impact work quality, the number of managers who were considering implementing a four-day work week was almost double that of those who weren’t (42.1% versus 26.1%, respectively). Just over one-quarter were already working four-day weeks occasionally, while 5.9% had implemented a four-day week consisting of 10-hour days.

Skynova offers resources for small businesses to streamline their finances, like invoice templates, organizational tools and accounting software.

This study uses data from a survey of 1,001 employees and managers located in the U.S. Survey respondents were presented with a series of questions, including attention-check and disqualification questions. 54.6% of respondents identified as men, while 45.4% identified as women. Respondents ranged in age from 31 to 71 with an average age of 48. 38% of respondents worked in a managerial position, while 62% worked on a non-managerial level. 21.3% of respondents were Gen Zers, 33.1% Millennials, 34.2% Gen Xers, and 11.4% were baby boomers. Participants incorrectly answering any attention-check question had their answers disqualified. This study has a 3% margin of error on a 95% confidence interval.

Additionally, this study uses data from the 2021 bureau of labor statistics on full- and part-time employees in the U.S.

Please note that survey responses are self-reported and are subject to issues, such as exaggeration, recency bias, and telescoping.

We freely offer our study’s findings for employees, managers, business owners, and anyone else it may benefit. If you would like to share any information from this article, we ask that you only do so for noncommercial purposes, and please credit us by including a link back to this page.