|

With staff shortages aplenty due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, employers are struggling to ensure that all the necessary work gets done. When hiring new people isn’t an option, making current employees work overtime is an obvious solution. However, workers aren’t necessarily willing to put in the extra mile out of the goodness of their heart. To learn more about workplace perspectives on mandatory overtime, we interviewed 800 employees and 200 employers to get both sides of the story.

In the article below, we discover whether it’s possible for employees and employers to find common ground on this topic. For example, what kind of benefits do employees need in order to feel that overtime work is worth their time and effort? How comfortable are employers imposing mandatory overtime? Read on to find out more.

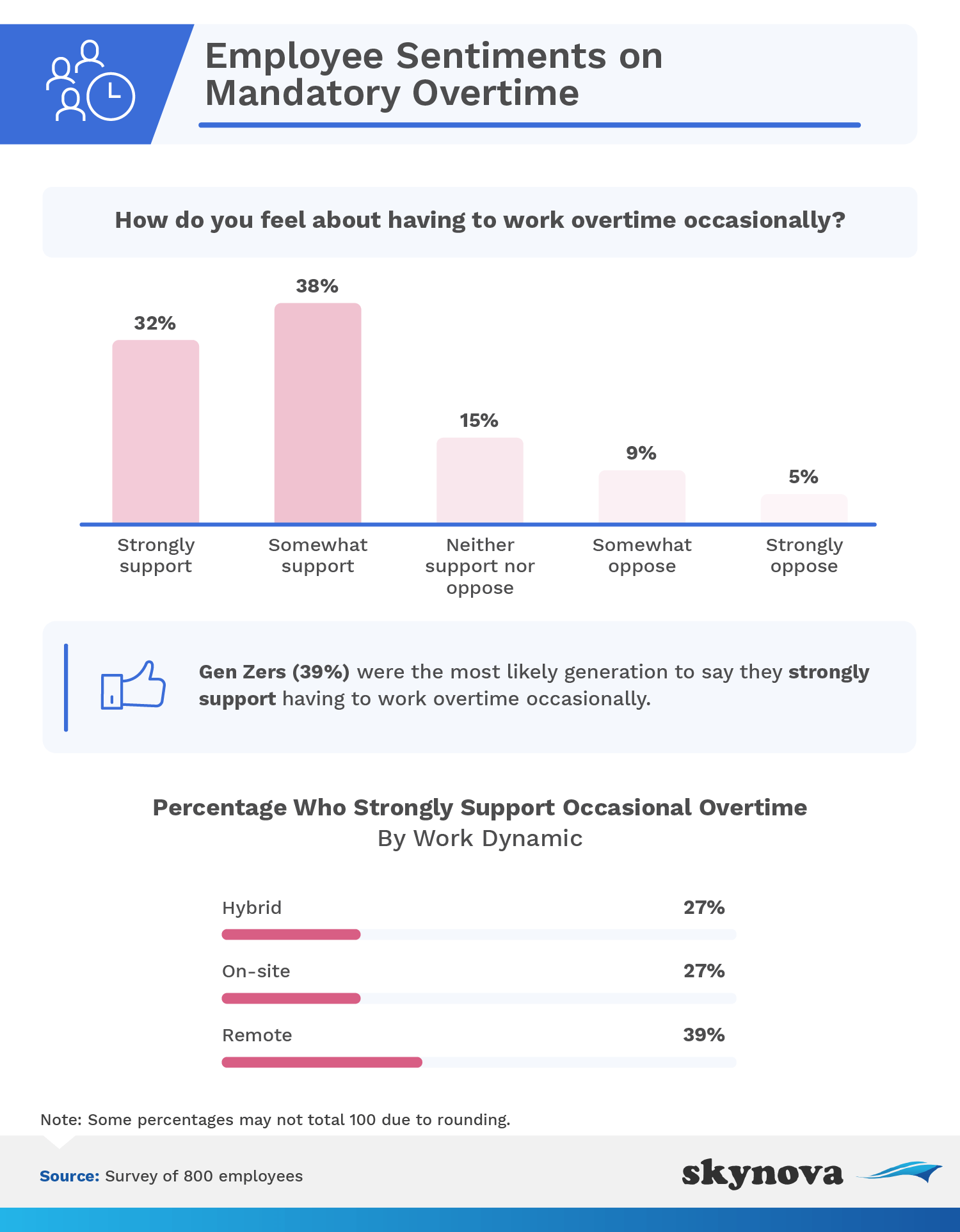

Most respondents actually didn’t mind working overtime on occasion. Thirty-eight percent somewhat supported the concept, while nearly a third had no problem with it at all. Gen Zers were the most open of all generations to working longer hours if need be. More work usually equals more money — this, along with the opportunity to prove their commitment to the company, inevitably appealed to young and hungry workers trying to build a strong foundation for themselves and their careers.

By work situation, respondents who operated remotely felt better about working overtime than people in hybrid or on-site circumstances—probably because it’s more manageable to work late from the comfort of your own home. By industry, 38% of employees working in education and government supported occasional overtime, whereas the same could be said for 36% and 31% of people in health care and information technology, respectively.

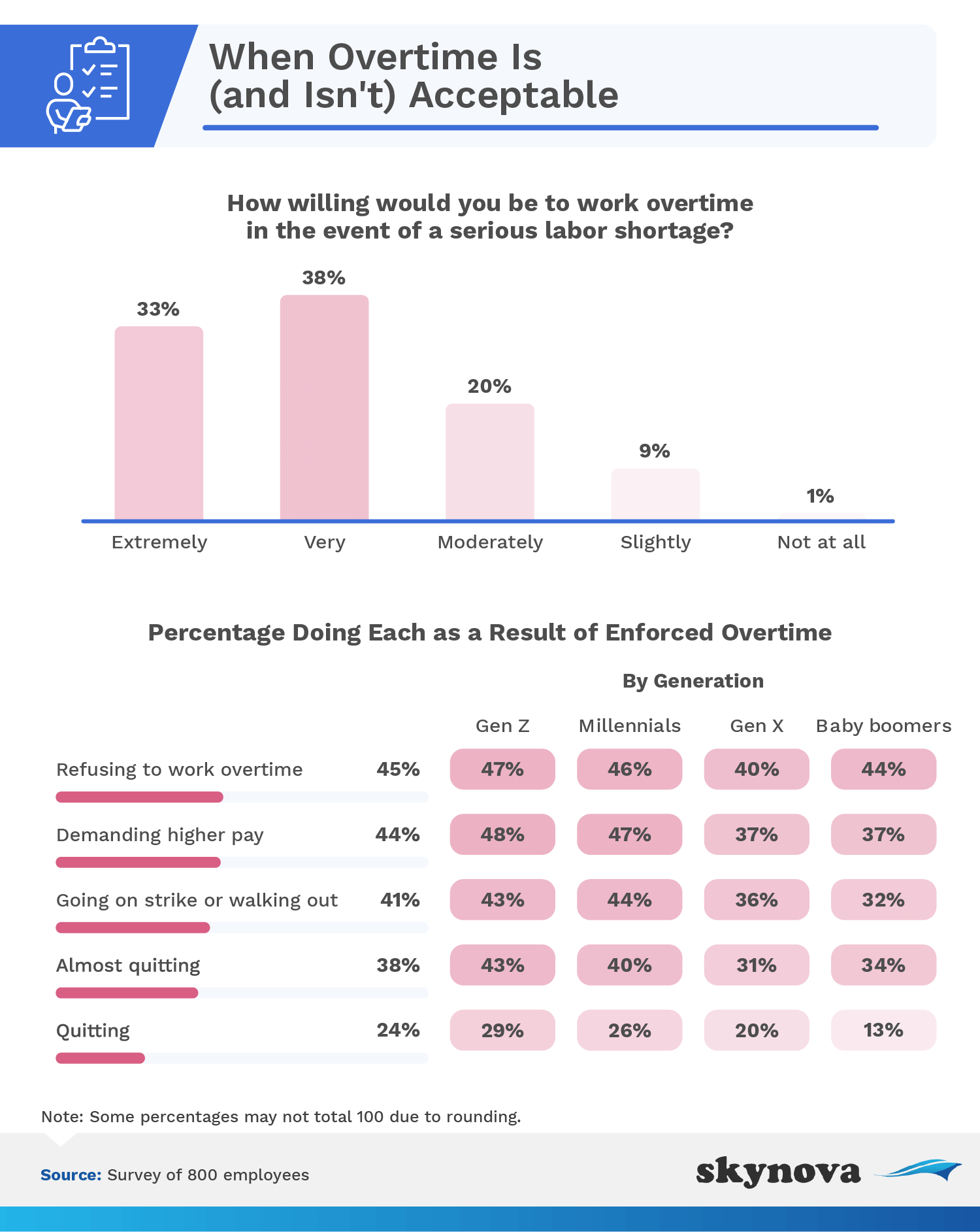

If a labor shortage left an employer in dire need, most people wouldn’t have an issue with going the extra mile—in fact, only 1% of respondents were not at all willing to do so. However, that didn’t mean they were always happy to work additional hours.

Of the respondents who had been in a situation where mandatory overtime was imposed, 45% simply refused to comply. Otherwise, 44% rightfully demanded higher pay, 41% either went on strike or walked out on their employer, 38% considered quitting, and 24% decided to take the leap and resigned. Interestingly, for all responses except demanding higher pay, remote workers were much more likely to put their foot down than hybrid and on-site workers.

Notably, Gen Zers were the most likely to demand higher pay as a result of mandatory overtime—proving that although they were the most likely to support working overtime occasionally, money was an important part of the equation. Gen Zers and millennials were also the quickest to consider walking out on an employer or even quitting in the face of mandatory overtime. Overall, employees leaving their job in pursuit of a better work situation as a result of their employer’s response to the pandemic has become so commonplace that there is now a name for it: the Great Resignation.

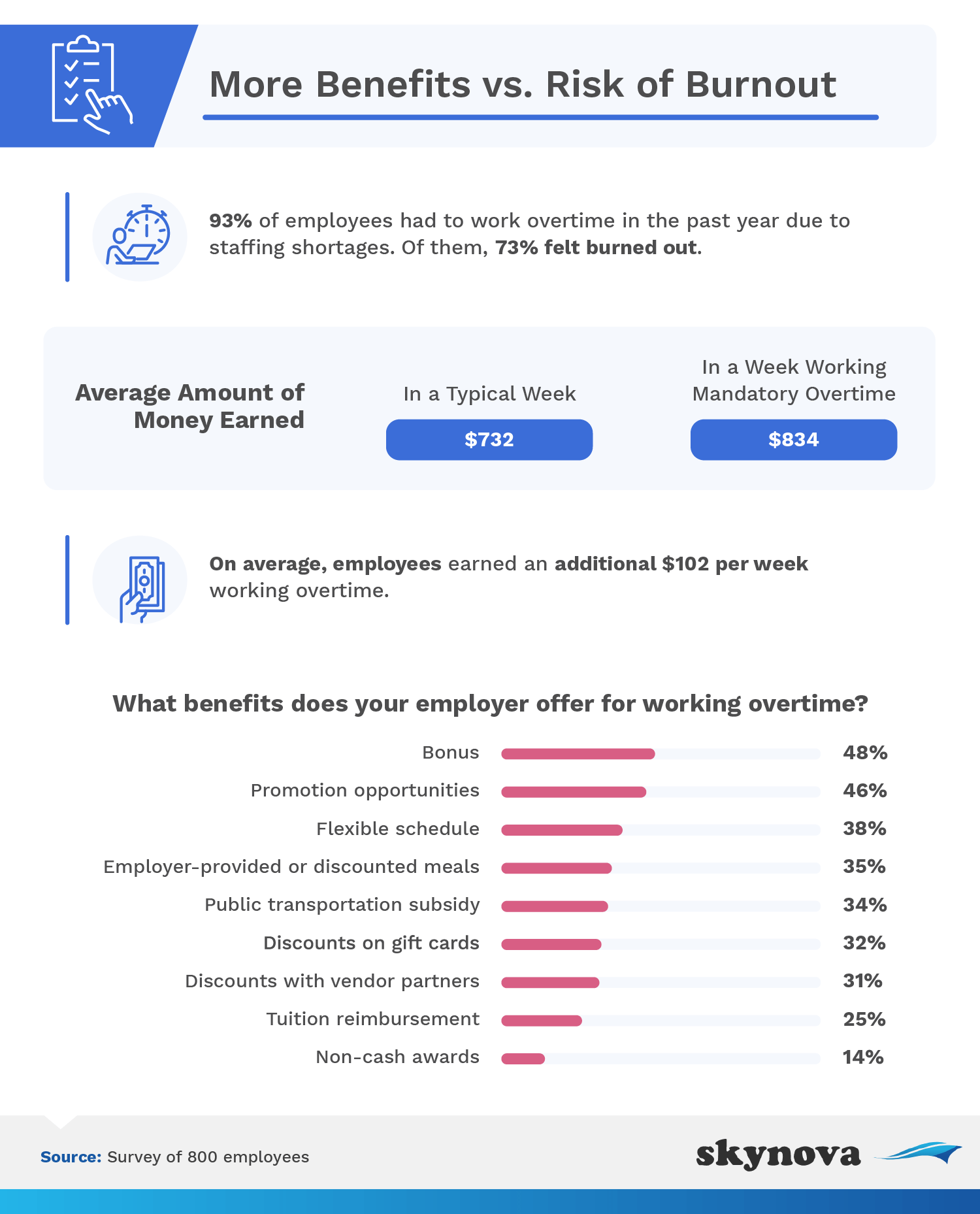

For those who stick with their jobs, working overtime may mean more money, but it can also come with serious downsides. Burnout, health consequences, and a general reduction in one’s quality of life are all reasons why people might react negatively to overtime, especially if it’s mandatory.

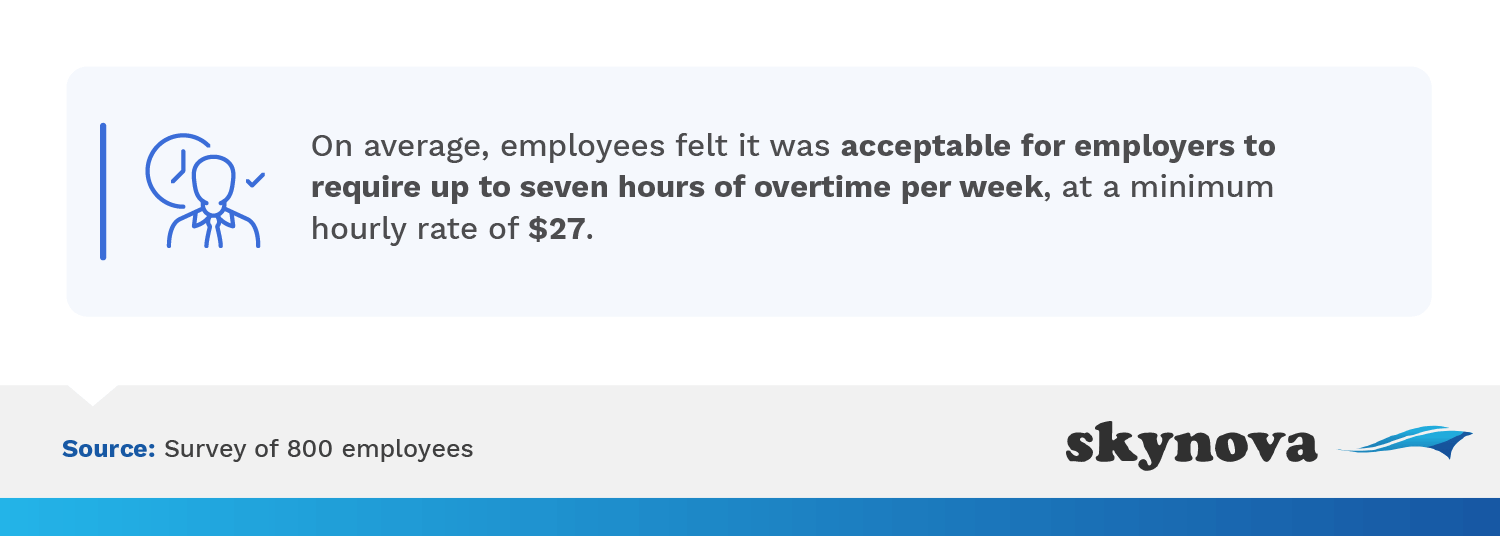

Workers clearly laid out what they’d need for overtime work to be a feasible part of their job. On average, they would happily accept up to seven overtime hours a week—with the caveat that they were paid a minimum of $27 per hour. Seeing as the federal minimum wage in the U.S. is $7.25 per hour, employees wanted a big boost in exchange for their after-hours services.

Due to the staffing shortages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, 93% of the employees we surveyed had to work overtime in the past year. Of them, nearly three-quarters had experienced burnout, which can lead to a number of different physical and psychological problems.

In a week that involved working mandatory overtime, respondents made just over $100 more than they would on a regularly scheduled week on average. Money is definitely a good incentive for getting employees on board for overtime work, and the top benefit offered by employers was indeed a bonus. Other popular incentives included promotion opportunities, flexible schedules, and a number of discount-related perks.

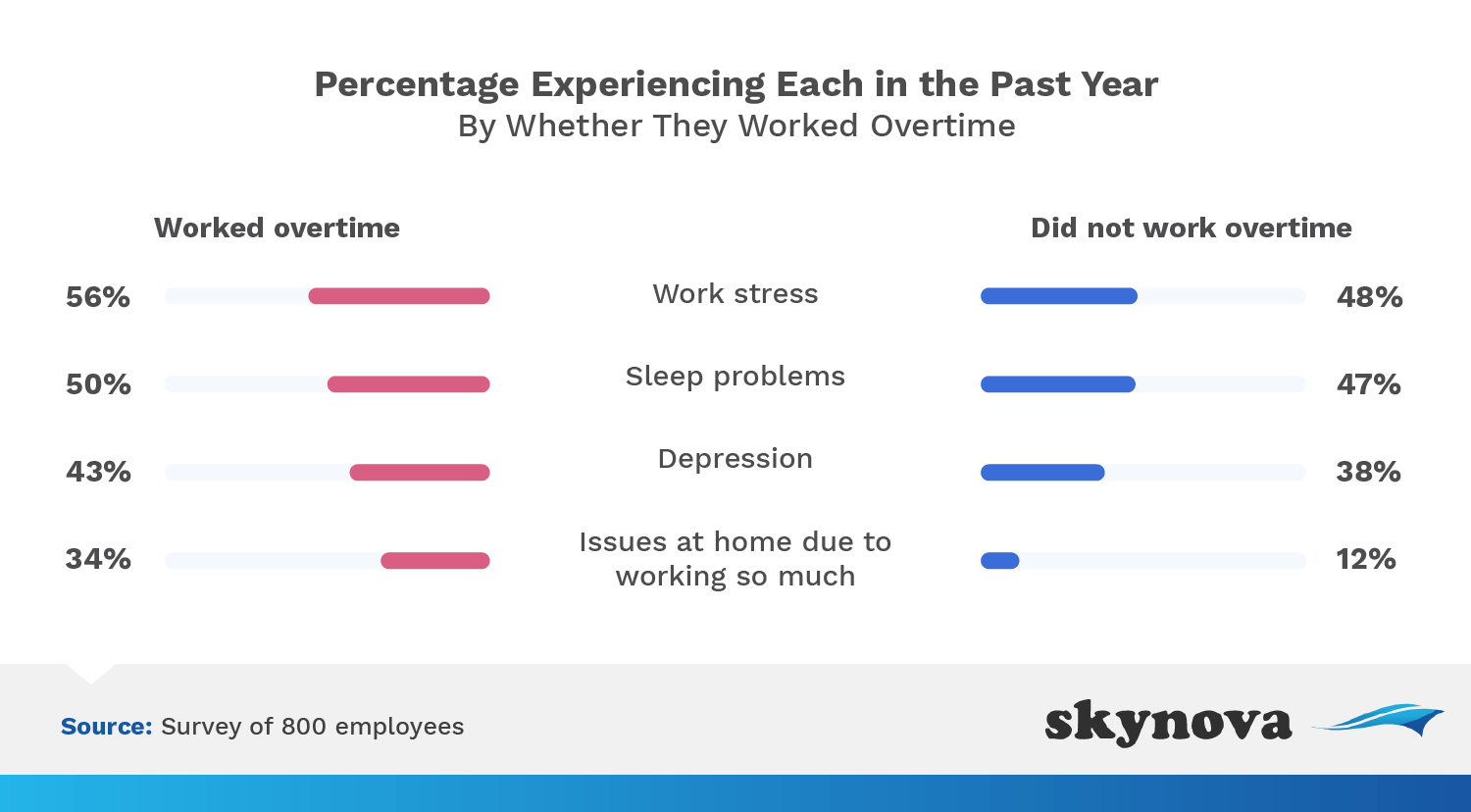

Whether they worked overtime or not, employees all over the country exhibited similar levels of work stress, sleep problems, and depression (although those who did work overtime were more likely to report all three).

People who were clocking in the extra hours reported significantly more issues at home than those who weren’t, though. More time at work means less time for your loved ones—and the additional time away paired with increased stress can spell trouble for the people that depend on you (and for the people that you depend on).

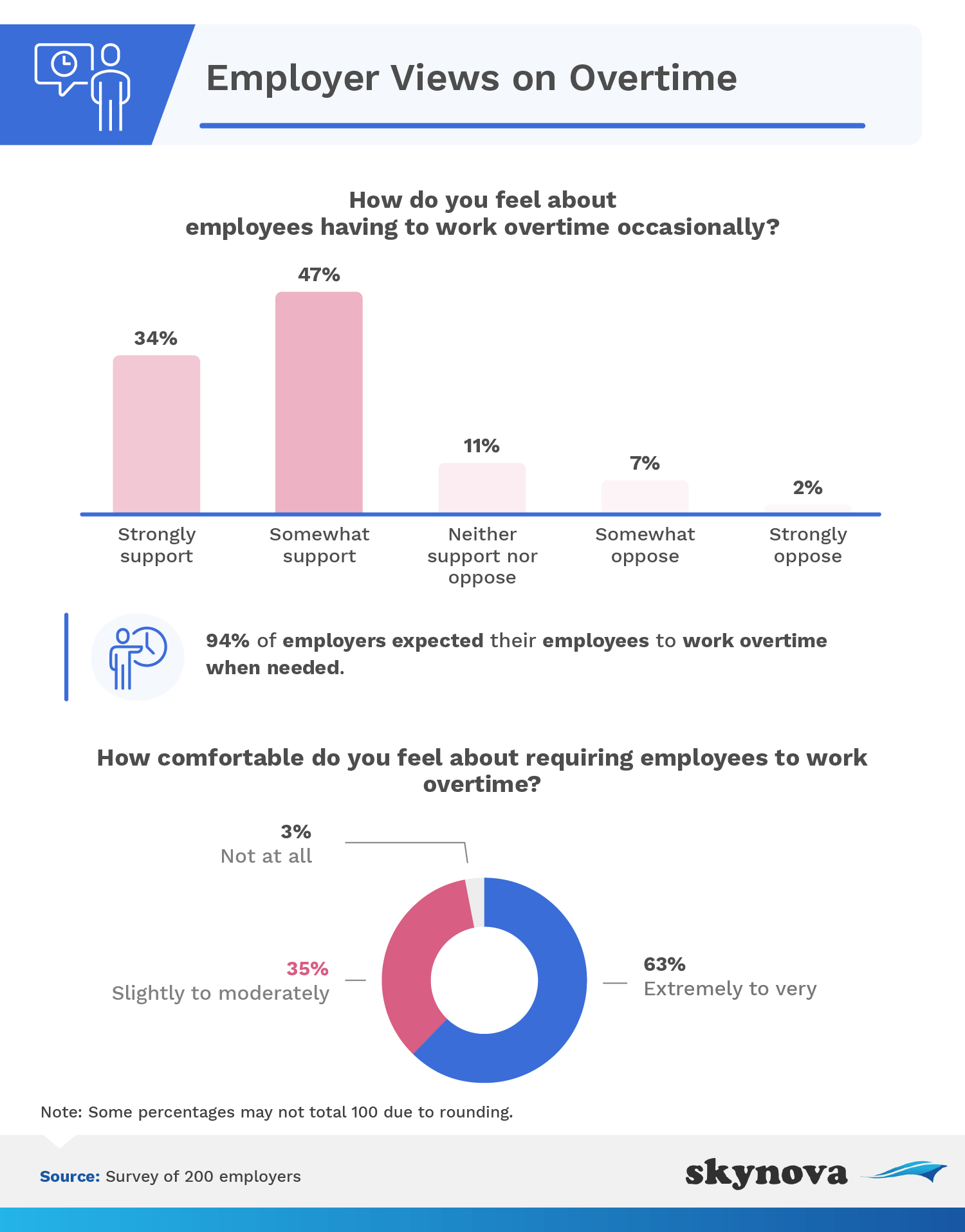

The next section of our study focuses on the employer perspective. When asked about the extent to which they supported employees working overtime occasionally, answers were similar to those given by the employees themselves. Most either somewhat (47%) or strongly (34%) supported the idea, and only a select few were vehemently against it. In a time of need, almost all employers (94%), and especially those in health care (97%) and information (96%), expected their subordinates to take on overtime work—no questions asked. There was a drop-off in support on the topic of required overtime, but 63% of employers still believed that it was fair to impose it.

In times of hardship, the majority of employers felt very or even extremely comfortable asking employees to go the extra mile. To get the best possible response to an overtime work request or demand, employers should make sure they’ve developed prosperous relationships with their workers. Being authentic, consistent, and flexible are a few ways to ensure that your employees feel like they’re working hard not because they have to, but because they want to.

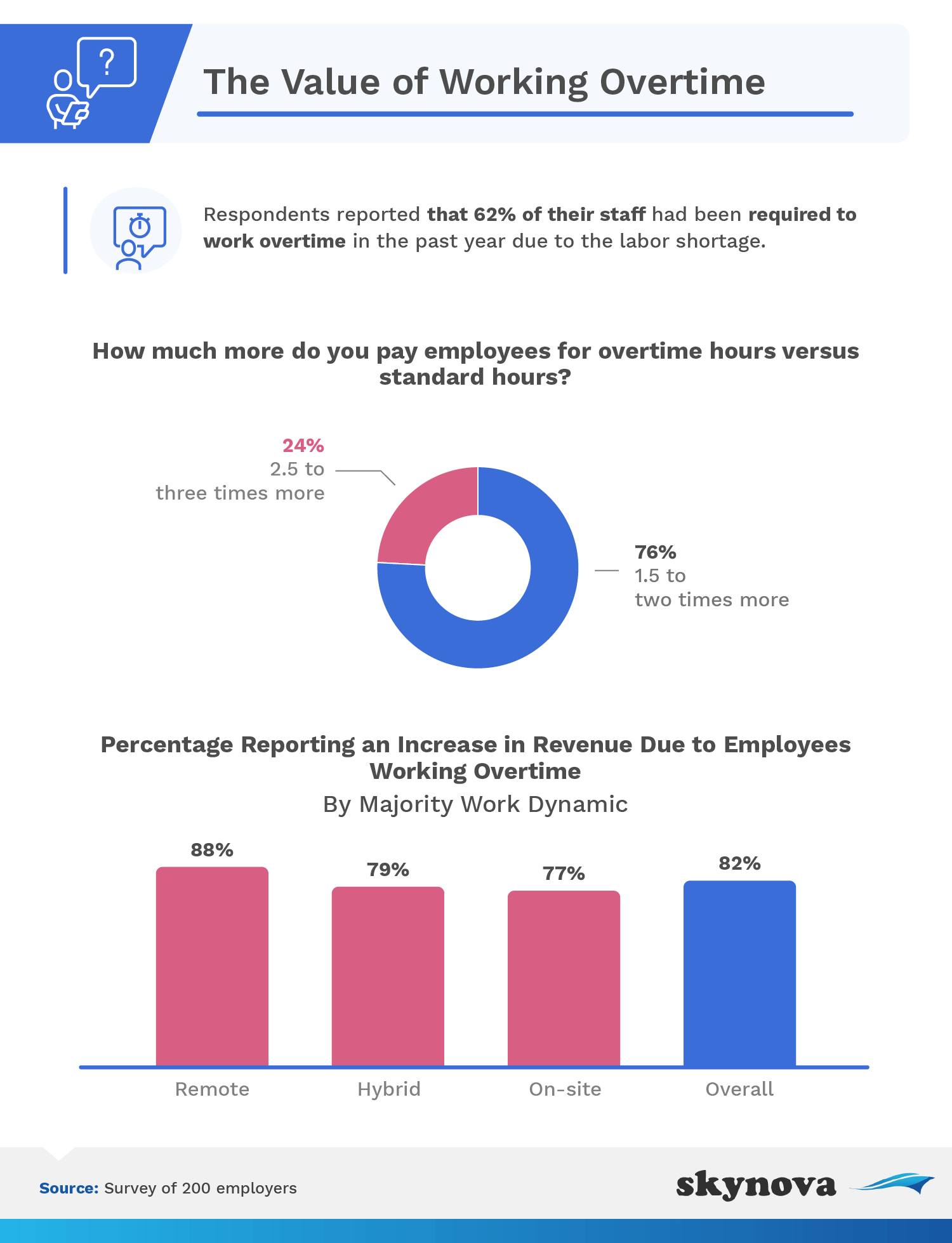

Overall, employers reported that 62% of their workforce had been required to work overtime in order to make up for staff shortages over the past year. This number rose to 67% for those in the health care industry and to 64% for those in information technology.

As we know, the extra work isn’t done for free — just over three-quarters of employers reported paying their staff somewhere between 1.5 and two times more than usual for working overtime; while just under a quarter paid 2.5 to three times more.

Eighty-two percent of employers reported that their company’s revenue increased due to the extra hours staff put in.

Generally speaking, most employees were OK with working overtime on occasion, especially those who work remotely. This sentiment held if employers were in desperate need of the extra help. On average, employees agreed that seven hours of overtime a week was fair, and that they wanted a minimum of $27 per hour. Other incentives that employers used to sweeten the deal included bonuses, promotion opportunities, a more flexible schedule, and a plethora of discounts. However, there was a very different response when respondents were faced with excessive mandatory overtime. Outright refusing to work, demanding higher pay, threatening to quit, and actually quitting were all common outcomes.

If an employer can strike the perfect balance of manageable overtime hours and fair incentives, both parties reap the benefits—including increased company revenue.

Skynova’s many online software modules make all the accounting needs for small businesses a breeze. Separate from our product, we like writing in-depth articles about topics that we, and hopefully you, find engaging. Our pieces usually have a business or workplace angle, and tend to tie in with another area of society. We construct our articles using both primary sources (i.e., surveys) and secondary ones (i.e., statistics and research) to ensure that we produce rich content with novel insights and perspectives.

We surveyed 800 employees and 200 employers about their perspectives on mandatory overtime. Among employees, 62% were men, and 38% were women. Employee ages ranged from 25 to 59 years old with a median age of 37. Among employers, 65% were men, and 35% were women. Employer ages ranged from 25 to 60 years old with a median age of 36.

For short, open-ended questions, outliers were removed.

To help ensure that all respondents took our survey seriously, they were required to identify and correctly answer an attention-check question.

Survey data have certain limitations related to self-reporting. These limitations include telescoping, exaggeration, and selective memory. We didn’t weight our data or statistically test our hypothesis.

If you know someone who’s ever worked overtime or simply wants to learn more about what it entails, we encourage you to send them this article for any noncommercial use. We just kindly ask that you include a link back to this page so they have access to the full scope of our findings and methodologies.