|

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted virtually every area of life in 2020, and as many Americans are realizing, those changes may not go away after the virus has passed. After months of living in various stages of lockdown and self-quarantine, perhaps one of the biggest shifts caused by COVID-19 has been in the workplace. And while some of those changes may be obvious, with millions of Americans working from home and ongoing efforts to social distance in public spaces, there’s a somewhat quieter tension occurring behind the scenes for many.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced millions of working parents to confront the child care crisis occurring in the U.S. in a whole new way, driving women out of the workforce in alarmingly high numbers and forcing others to reevaluate their professional commitments.

For an even closer look at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on working women (including those with and without children), we analyzed data from the Basic Monthly Current Population Survey (CPS) and we surveyed over 1,000 employed women for their perspective on balancing life and careers in 2020. Read on as we explore how many extra hours women are working across a variety of industries; which states have the longest average workweeks; where working mothers are finding outside help; and how the COVID-19 pandemic may change the way women without children view their ability to juggle work and life.

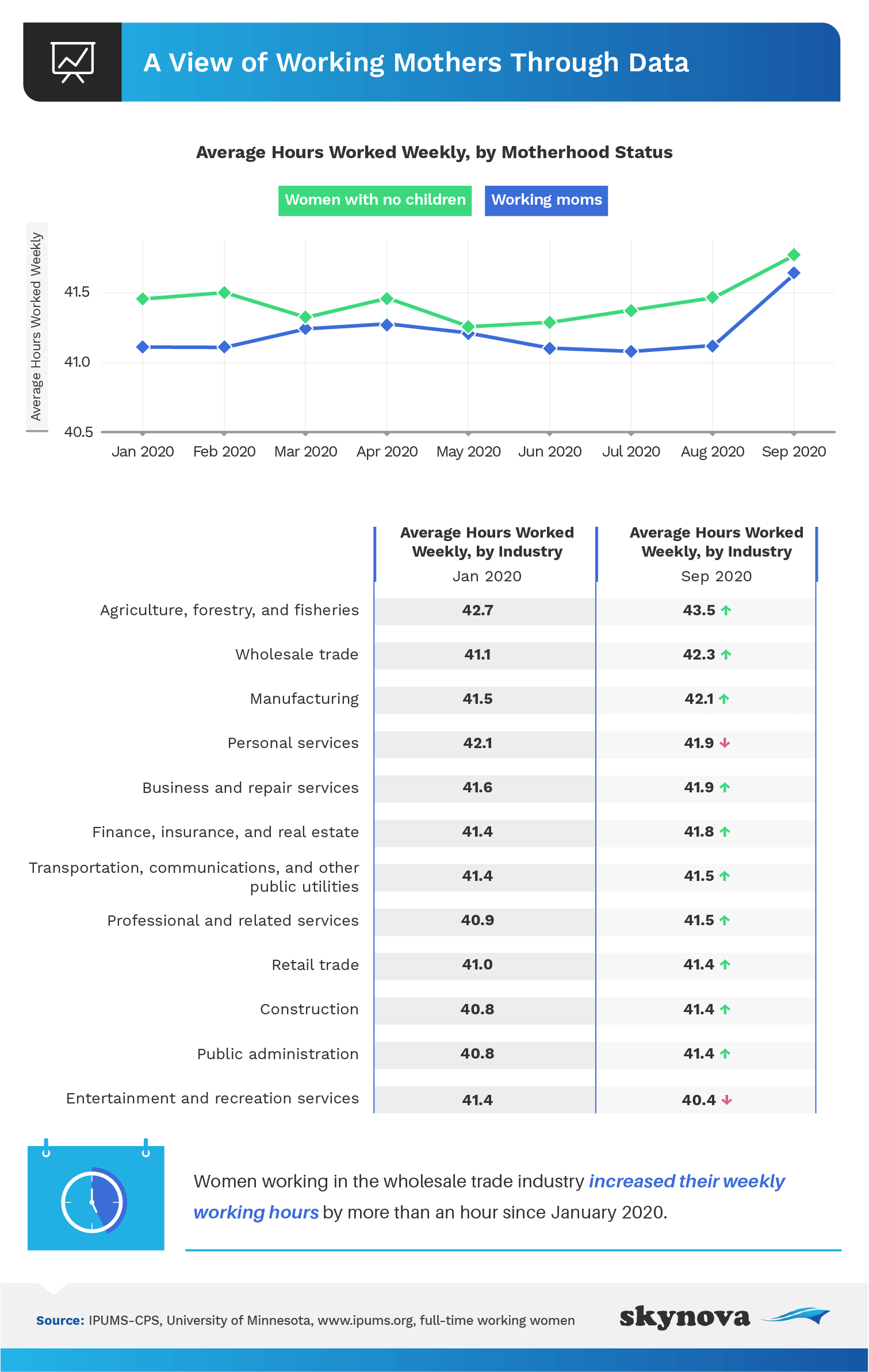

In September 2020, both women without children and working mothers worked more hours per week, on average, than they did in January 2020. In the early months of the pandemic, while women without children saw a slight decrease in the number of hours they were putting in each week, women with children saw those hours rise. As adults adjusted to changes in their working environments, parents also experienced major shifts in child care after the pandemic began, with many either unable to find available care options or unable to afford them.

Zooming in on the average number of hours women have been working in 2020 by industry, we found the biggest increases between January and September in wholesale trade. In addition to the global economic decline triggered by the pandemic, the wholesale trade industry has been looking toward the implementation of technology to help increase efficiency and streamline operations. Despite the opportunities offered by advancing digital capacity in the corporate world, these adjustments can also be difficult to adjust to, requiring more effort from businesses and their employees to adapt.

Other notable increases in the average hours worked among women between January and September 2020 occurred in manufacturing, professional and related services, construction, and public administration.

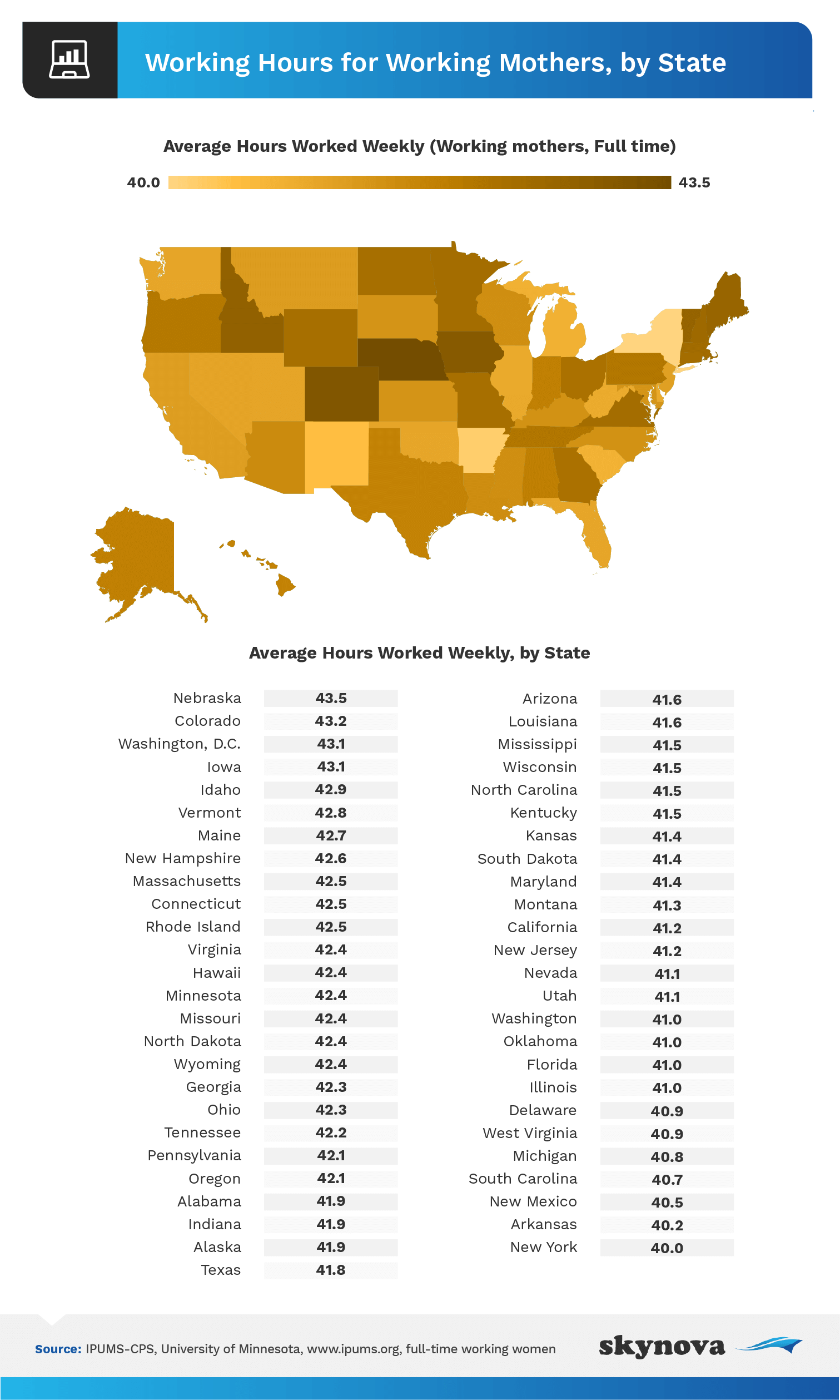

So where are working mothers putting in the most hours? Despite the near-universal struggle among women to balance their working careers and life at home as a parent, we found the longest average workweeks in Nebraska (43.5 hours), Colorado (43.2), Washington, D.C. (43.1), and Idaho (42.9).

In 3 out of the 5 states with the highest average hours worked per week, we found between 8% and 10% of working mothers in manufacturing jobs, an industry that has been plagued by job loss as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. As previously indicated, manufacturing jobs have also seen longer workweeks for women between January and September 2020, perhaps as companies load balance work with reduced staff. While professional and related services was the most common industry for working mothers in these states, we also found roughly 1 in 10 (or more) women with children in states with the highest working hours in retail positions. Not unlike manufacturing jobs, retail workers have experienced massive job cuts as a result of the pandemic, in addition to remaining employees being forced into new roles or positions as companies pivot to online sales and e-commerce.

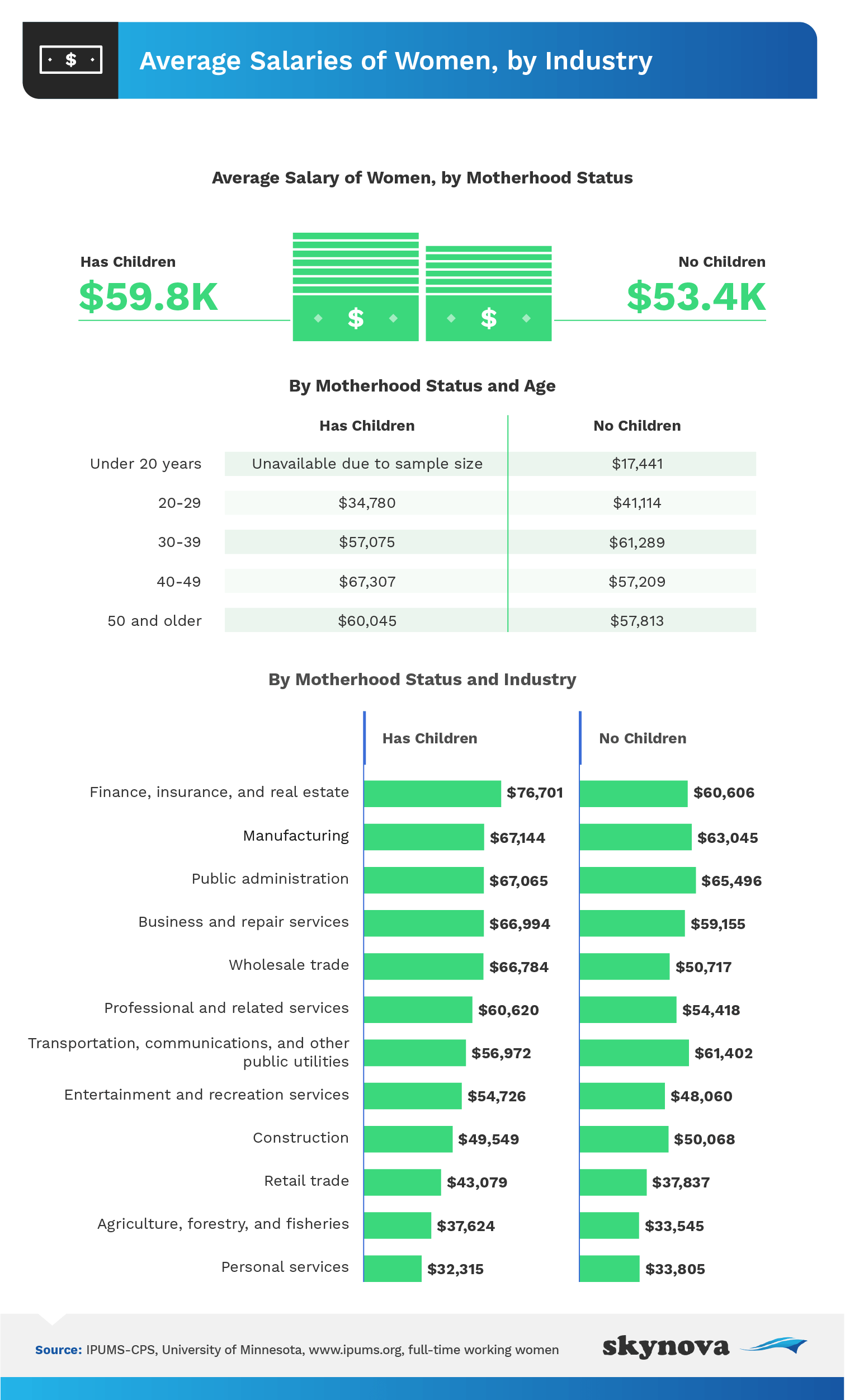

According to data from the Basic Monthly Current Population Survey, those with children earned higher salaries ($59,800) compared to those without ($53,400), except among women under the age of 39. In contrast to women between the ages of 40 and 49 years old, we found women without children between the ages of 20 and 29 earned over $5,000 more annually, on average, than those with kids, and women without children between the ages of 30 and 39 earned over $4,000 more, on average.

And while women with children clearly earned higher average salaries in some industries (including finance, insurance, and real estate), there were other industries where their average salaries were considerably lower. In transportation and communication jobs, women without children earned $5,000 more, on average, compared to those with kids. Similarly, we found annual salaries were higher in construction jobs for women without children versus working mothers.

It’s worth noting that while women with children earned more than those without kids in many industries, parents also have the added cost of child care to consider as they balance work and home life. In the U.S., the cost of child care can be as high as $20,000 a year in some states, depending on the child’s age. For many professional women transitioning to working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, some parents have to decide between maintaining their jobs or caring for children who are also learning remotely. In these cases, the cost of child care can be prohibitive to remaining in the workforce. Between August and September 2020, over 860,000 women exited the labor force completely.

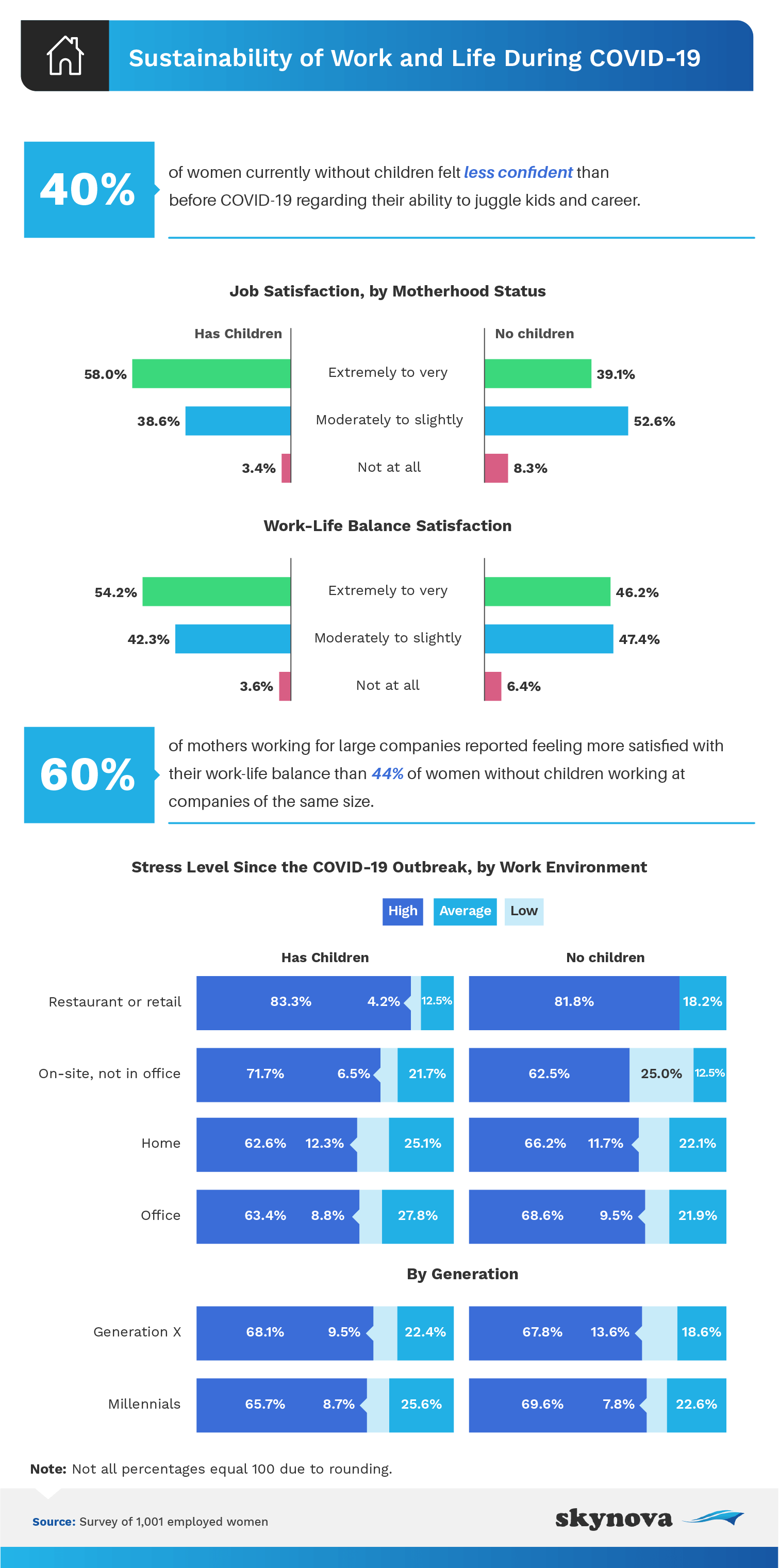

As we found, 40% of women without children feel less confident than before COVID-19 about their ability to juggle both children and a career. Despite these concerns, working mothers surveyed were 19 percentage points more likely than women without kids to report being very to extremely satisfied with their jobs and 8 percentage points more likely to indicate they were happy with their work-life balance. In contrast, women without children were twice as likely as mothers to report not being happy with their jobs at all and nearly as likely to be completely dissatisfied with their work-life balance.

Sixty percent of mothers working for large companies reported feeling more satisfied with their work-life balance than 44% of women without children working for similar companies. As an example of the work companies are doing to help parents balance work and home life, Google employees were given 14 weeks of paid leave to manage family responsibilities, and at Target, parents were given the opportunity to take advantage of backup child care options paid for 20 days.

Women with children were more likely to report higher levels of stress since the COVID-19 pandemic in certain industries, though, including restaurant and retail jobs, or other on-site (but not in-office) positions. In contrast, women without children working from home had slightly higher stress levels, in addition to those working in office jobs.

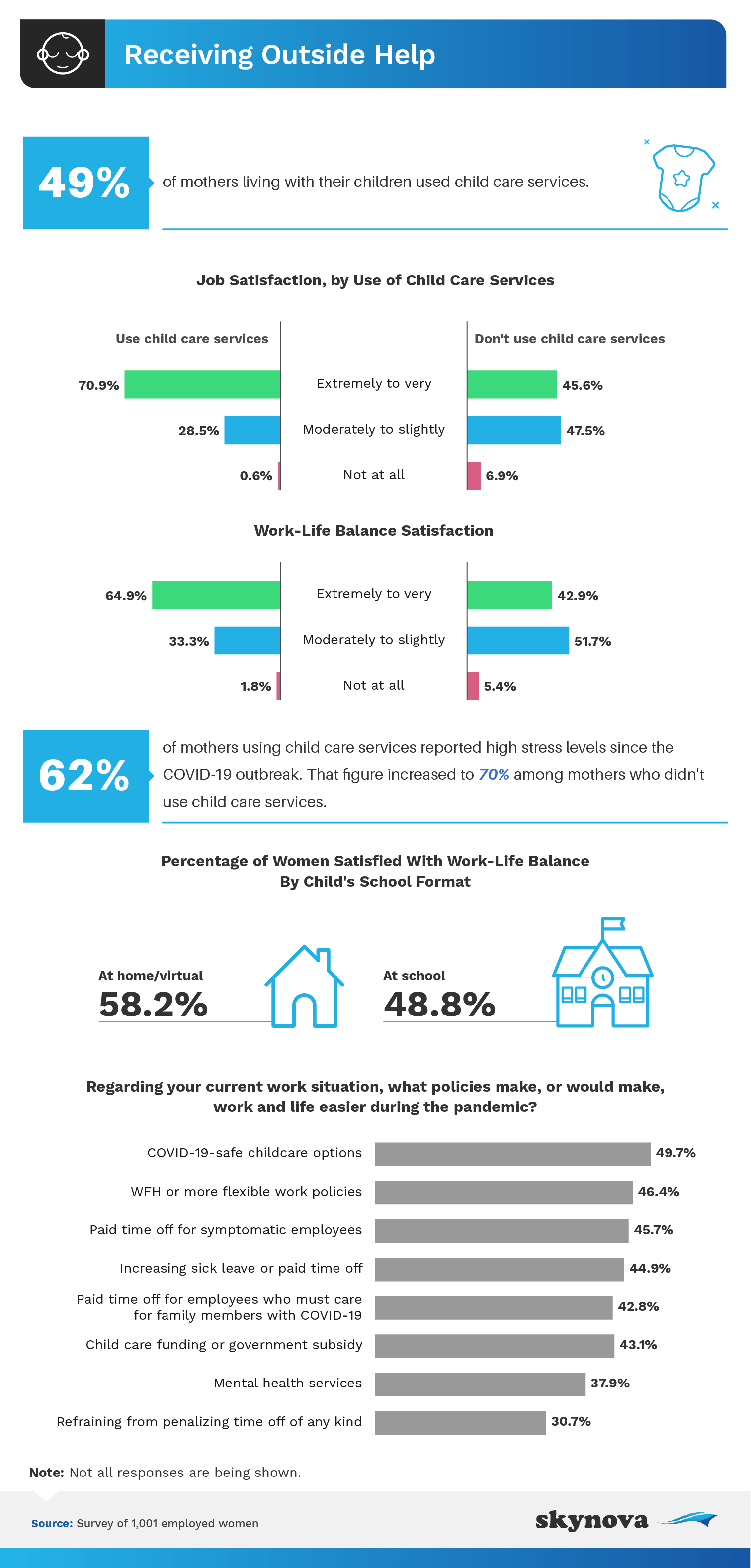

While mothers generally reported higher levels of satisfaction with their jobs and their work-life balance, that happiness might be contingent upon having access to child care services. Compared to 71% of mothers receiving child care services who indicated being very to extremely happy with their jobs, just 46% of mothers without child care said the same, and 48% were only slightly to moderately satisfied. Seven percent of mothers with children living at home and without access to child care indicated they were not at all satisfied with their job.

We found similar trends for work-life balance as well. Women with children living at home and without access to child care were 19 percentage points more likely to be just slightly or moderately satisfied with the balance they’d found and three times as likely to be not at all satisfied.

Mothers were also more likely to be less satisfied with their work-life balance when they had children attending brick-and-mortar schools versus distance learning. Mothers also reported that COVID-safe child care options (50%), more flexible work-from-home policies (46%), paid time off for symptomatic employees (46%), and increasing sick or paid time off (45%) would be the most helpful for adjusting to life during the pandemic.

Millions of working Americans are adapting to life during the COVID-19 pandemic, and for many, that’s meant major overhauls, including working from home for the foreseeable future, engaging with technology in new ways, and working longer hours. For women, particularly working mothers, the challenges are exacerbated by the challenge to balance both work and home life as never before.

While mothers were more likely to report being happy with their jobs and their work-life balance than women without children, we found that satisfaction was largely reliant on having access to child care for working mothers. Among those not using child care services, both job satisfaction and work-life balance were significantly lower. And while compensation may be higher, on average, for women with children, those increases in pay may not be sufficient to cover the annual cost of child care for young children.

With 37 unique software modules, Skynova solutions are designed specifically with small businesses in mind to help you manage all of your accounting needs. Designed to work independently or together, we help businesses modernize and simplify their invoices, subscription services, retainers, work orders, and billing needs. In addition to these products, we also compile research like the findings found in this study that are relevant to business owners and provide a fresh perspective on new and ongoing workforce trends. Our mission is to help make business easier for small firms, letting them focus more on what matters most in today’s climate.

We surveyed 1,001 women employed full time to explore how they balance their work-life and how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted them. Of our respondents, 100% were women. The average age of respondents was 37 with a standard deviation of 10.

For short, open-ended questions, outliers were removed. To help ensure that all respondents took our survey seriously, they were required to identify and correctly answer an attention-check question.

These data rely on self-reporting by the respondents and are only exploratory. Issues with self-reported responses include, but aren’t limited to, the following: exaggeration, selective memory, telescoping, attribution, and bias. All values are based on estimation.

This project also incorporated data from the Basic Monthly Current Population Survey (CPS), conducted by the United States Census Bureau. The CPS surveys around 60,000 households across America, during which households are surveyed for four consecutive months, take a break for eight months, and then are surveyed again for an additional four consecutive months. After that point, a household leaves the sample permanently. We explored variables specifically related to women with children, who also reported they were employed. We looked at the ASEC, an economic supplemental survey, to determine salaries as they related to industry. We also looked at variables in which respondents reported their “usual hours worked” at their main job to determine what the hourly demands were on working mothers.

We encourage you to share these findings on women in the workplace during the COVID-19 pandemic with your readers for any noncommercial use simply by including a link back to this page in your story so they have access to our full report and research methods.